In Japanese aesthetics, the phrase “mono no aware” means “the poignancy of things.” The photograph (of part of our garden) represents this sentiment. Nothing is contrived, set, posed, overstated, exaggerated, or intrusive–nature found as it is. The creatures hold their beauty naturally: Monarch butterfly and echinacea flower, two of nature’s most beautiful creatures. At that moment of apprehending beauty we also realize vulnerability, which is intrinsic to the reality of the creatures. This vulnerability is itself their evanescence (not yet realized).

And this is the poignancy of the fortuitous moment of the photograph. The poignancy of things is the beauty, the vulnerability, and the evanescence. The next day, the flower dessicates, its petals fall, the stalk bends, and the butterfly does not return to the garden.

We can further understand aesthetic components: wabi, sabi, and yugen. Wabi is the starkness of the moment’s reality. Striking, exciting, breathtaking, surprise at being present. Wabi is the solitude character of the moment, nothing intruding, enhancing or contriving a more companionable or acceptable projection of awareness. A moment that needs nothing, no articulation, no description. Sabi reflecting the simplicity of elements, the natural appearance of butterfly and flower, the shape, color, light, none of it contrived, all trembling in a convergence brought into being, before our sight, as if just for oneself. Yet the present is laden with our realization that the moment cannot last, even before us, that it cannot last, that we must or will move on. Finally, yugen is the fact (“facticity”) of this total convergence of nature and reality, a moment to be not simply apprehended, comprehended, taken in, awed by, but from which we can learn the very heart of things.

Gardens

The formal gardens of history were never intended to be places of respite and tranquility, rather the opposite. The formal gardens of Mesopotamia, Persia, later Spain and France, among others, were secluded spaces projecting the power of its resident monarch or autocrat, the aloofness and protected status of emperor and court.

Though the Garden of Eden was described as Paradise, the origin word “paridaiza” is the Persian term for “walled,” as in walled garden, a paradise for the ruler but not for a subject. The image of Eden depends upon its naive residents, not on the architect Yahweh, for its benignity.

The formal gardens are noted for symmetry and imposing dimensions, a large,forbidding landscape where ornament and artifice reign. For example, Xenophon records (in his book The Economist, 1 16-23) an anecdote of Lysander visiting Cyrus, the Persian emperor, and walking with the latter in his formal garden:

Lysander, it seems, had gone with presents sent by the Allies to Cyrus, who entertained him, and amongst other marks of courtesy showed him his ‘paradise’ at Sardis. Lysander was astonished at the beauty of the trees within, all planted at equal intervals, the long straight rows of waving branches, the perfect regularity, the rectangular symmetry of the whole, and the many sweet scents which hung about them as they paced the park. In admiration he exclaimed to Cyrus: “All this beauty is marvellous enough, but what astonishes me still more is the talent of the artificer who mapped out and arranged for you the several parts of this fair scene.” Cyrus was pleased by the remark, and said: “Know then, Lysander, it is I who measured and arranged it all. Some of the trees,” he added, “I planted with my own hands.” Then Lysander, regarding earnestly the speaker, when he saw the beauty of his apparel and perceived its fragrance, the splendour also of the necklaces and armlets, and other ornaments which he wore, exclaimed: “What say you, Cyrus? Did you with your own hands plant some of these trees?” whereat the other: “Does that surprise you, Lysander? I swear to you by Mithres, when in ordinary health I never dream of sitting down to supper without first practising some exercise of war or husbandry in the sweat of my brow, or venturing some strife of honour, as suits my mood.” “On hearing this,” said Lysander to his friend, “I could not help seizing him by the hand and exclaiming, ‘Cyrus, you have indeed good right to be a happy man, since you are happy in being a good man.'”

Doubtless such conversations surrounded all of the monuments of imperial antiquity up to the present, for the formal gardens are not sources of food but confections flattering their resident and owner, reflecting the imagined wisdom of king and emperor. The walls keep curious onlookers and peasants out, as much as do the castle walls, the fortress walls, the palace court, and the dungeons.

We are a long way from simplicity, even from aesthetics. The formal garden is vulgar, pompous, and completely unnatural. Symmetry projects the appearance of marching troops. Walls repel outsiders and nature itself, while imprisoning subjects and oher creatures. We should not admire “paradises.” Will we pine after them when they are inevitably lost? Expend our energies maintaining them for someone else, or for some ideal or vanity? We are better left cultivating our garden, imitating nature, then looking at someone’s else and longing for it rather than working on ours.

The Taoists of ancient China wanted their rulers to be anonymous, because their pompous edifices were not to be seen, indeed, did not exist. The Taoist Tillers school proposed that the king not have his own fields and forests, let alone gardens, but work shoulder to shoulder with peasants in the field. Shen-gong, the mythical first king of the Chinese, was lauded for being a healer, herbalist, and farmer — unseen by anyone, so perfectly did the kingdom function.

Contrast the formal garden, too, with the simple hermit’s hut: Kamo no Chomei, describing his hut, casually notes: “To the north of my little hut I have made a tiny garden surrounded by a thin low brushwood fence so that I can grow various kinds of medicinal herbs.” Adding, “Such is the style of my unsubstantial cottage.” The Buddhist monk-hermit and poet Ryokan considered Dogen’s “celestial garden” too abstract, too formal, instead celebrating wildflowers and even the weeds that offended Dogen so much.

How, then, to “garden”? Grow what is essential, edible (even flowers), nourishing, and substantial. Let scale and dimension reflect need, not excess or appearance. Mingle vegetables with flowers in conviviality. Establish perennials, for they will establish themselves forever (well, for a few years!) and return in greeting every spring to celebrate the passage of time and tenacity. Let all flourish, picking what is to be consumed the same day. Let nature express aesthetics, without too much human contrivance. If there are rock borders let them be overrun by creeping thyme. If there are walls, let flowering vines flourish climbing them, as if to mock the false boundary between nature and gardener. Individual bed spaces will be overlapped by prolific and flourishing plants. Let those plants that demand space be given their due, that they may reciprocate. Adding space is better than constricting self-development.

Here is a snippet about the garden, by Kahlil Gibran, from his “Sand and Foam”:

In the autumn I gathered all my sorrows and buried them in my garden. And when April returned and spring came to wed the earth, there grew in my garden beautiful flowers unlike all other flowers. And my neighbors came to behold them, and they all said to me, “When autumn comes again, at seeding time will you not give us of the seeds of these flowers that we may have them in our gardens?”

Buddha’s method

One of the strengths of historical Buddhism, as reflected in the Pali canon, is its suspension (formal and real) of metaphysics and speculation. To Western thinking, metaphysics and speculation about meaning and intention is core to philosophy. So, too, is its opposite. When it doesn’t get its way, that is, discovers and judges inadequate or unproductive metaphysics, the western reaction is swift, hostile, and dismissive (early Wittgenstein and his succession, logical positivism, etc.). Accordingly, the philosophy project is abandoned, withered, banished in overreaction.

Can there be a calmer, less passionate or emotive approach? That, perhaps, is the Buddha’s approach, not dismissive and hostile about the “wrong answer,” but attempting to understand the root of the desire for metaphysics, for speculation. Not that Buddhist thought lingers with these historical investigations. Rather, it moves directly to the more pressing issues versus the war between metaphysics versus anti-metaphysics.

The teaching method of the historical Buddha meant that priority could be given to the people, to their concerns, to humble listeners as much as to any wealthy critics. The emphasis of philosophical questions could be turned away from abstract quest for presumed meaning to questions arising from daily life. A virtual checklist of the Buddha’s method is provided in a snippet of dialogue between the Buddha and visiting Kalamas called the Kalamas Sutta or Aṅguttura Nikāyaṅ.

The dialog opens with the remark by the visitors that they have heard the teaching of certain “ascetics and brahmins” that ended by vilifying all who disagree with them. This had happened more than once. Being “ascetics and brahmins” the visitors naturally gave these teachers some deference but were clearly uncomfortable. They had come to the Buddha for advice. And that advice is clear, resonating over the centuries:

Do not go by oral tradition, by lineage of teaching, by hearsay, by a collection of texts, by logic or inferential reasoning, by reasoned cogitation, by the acceptance of a view after pondering it, by the competence of the speaker, or because you think, “the ascetic is our teacher.” But when you know for yourselves, “These things are wise, these things are blameless; theses things are praised by the wise, these things if undertaken and practiced, lead to welfare and happiness,” then you should engage in them.

These points can be broken down for clarity.

1. oral tradition –– received, repeated, familiar, original, memory

2. lineage of teaching –– the authority of the precept, commandment, injunction, argument

3. hearsay –– enough people say so, it is said that, majority opinion holds that …

4. collection of texts –– venerable scriptures from authorities of the distant past

5. logic or inferential reasoning –– collected accounts reflecting sound minds suggest that…

6. reasoned cogitation –– applied thought of disciplined, clear-minded insightful reflection

7. acceptance of a view after pondering it –– enough deep thinking suggests favorable weight

8. competence of the speaker –– clever and insightful expostulation persuades of the truth

9. deference to the teacher –– sincerity of heart carries the argument better than mere reason

If all of these approaches are inadequate to why metaphysics is our chief concern, then the opposite is that metaphysics is not our chief concern, is an abstraction, a distraction. The Buddha’s visitors are concerned about the essentials: why do we suffer, why do we get sick, grow old, and die. The question is not why these things but how we should test these essential factors in our lives, as a matter of time. The various observations of the Buddha constitute summaries of what his interlocutors distressfully say among themselves. The Buddha gives them the method: if these arguments or ideas bring contentment, then folllow them. If not, regardless of the nine points, don’t follow them.

The displacement of metaphysics with ethics is no subtle shift of attention but a focus on what matters here and now. Addressing everything in terms of ethical response guages what the interlocutors themselves want or note or value. Does this or that path or response lead to well-being and happiness? What is elicited by this behavior or mind-set versus that one? What happens when we universalize a particular frame of mind or emotion?

This Socratic-like discussion frees us from many strictures, of language, personality, authority, cultural society… at least as necessary or obligatory, if not inevitable. It teases out the true nature of behaviors and points to ethics as a psychological and social balance that is independent both of the enumerated points of view of reason and metaphysics and also independent of the degree of satisfactoriness of answers emerging from metaphysics and similar abstractions

The short version of the Buddha’s advice: test everything. Not to play science, which is itself a kind of metaphysics, but to drain all the accretions that clog the mind. Test everything. Does it bring insight, happiness, mental well-being? As the sutra says: “When you know for yourselves, ‘These things are wise, these things are blameless; theses things are praised by the wise, these things if undertaken and practiced, lead to welfare and happiness,’ then you should engage in them.”

The Way of April

The transition between winter and spring is especially erratic in a northern climate and elevation. One day the temperature reaches sixty degrees F. with a brilliant, cheerful sun. Surely spring has arrived!

The last of the snow melts. The timorous appearance of green in the garden emerges, from perennial chives and thyme, to the clueless garlic blinking through the straw and looking a blanched yellow from the lack of sunlight. After moving the straw, the garlic, too, is a vigorous green the next day.

But a few days later, several inches of snow fall. Dark clouds reign. A distinct chill returns, as do the additional layers of garments just put away for the arrival of spring. But the plants are hardy, patiently waiting as the snow quickly melts in the next day’s moderation, and the garden’s spots of bright green persist, a sign of resilience awaiting true spring.

One spot is, perhaps, not so fortunate. Down the road, concealed behind clumps of trees, a vernal pond has formed, arisen by recent rains and melted snow. Wood frogs and spring peepers have discovered the pool and vocalize loudly. Wood frogs hold their fascinatiopn — they survive the winter by allowing their bodies to freeze! Less dramatically, peepers join the wood frogs in raucous noise-making, celebrating reproduction, and survival until summer, or whenever the pool dries up. Another cold, dark day comes. The pool is silent. Are its denizens still alive? Who can know, until next spring, perhaps.

T. S. Eliot famously wrote, in The Wasteland, that:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Lilacs appear in the hint of warmth that is the transition to spring, but the unexpected return of snow and cold cruelly strikes down their effort. Or is this not the way it always is, only the foolish or the hardy braving the possibility of the cold returning, of the spring wavering in its intent, too tentative to emerge without fear. What psychological type best survives: the extrovert venturing into the world with the possibility of getting struck down, or the introvert watching critically and skeptically, waiting not for one sign or two but for an abundance that will confirm confidence in the world?

Or can the object of our venturing and watching ever be truly understood, ever be fathomed enough to discern a path, a way, a reliable truth?

Favorite hermits: 5. Ryokan

The Japanese hermit-monk Ryokan (1758-1831) is a favorite figure in Zen circles as a poet and monk — unexpectedly he is a favorite figure among Japanese schoolchildren. As a hermit, Ryokan regularly played with village children when he came to town to beg alms. Ryokan had stitched several balls of cotton for various games, enthralling the kids and often taking up much of a summer day, the absent-minded Ryokan occasionally forgetting to make his round of alms until late afternoon.

This generous gesture toward innocent children characterized all of Ryokan’s thinking. Someone called him a fool–it was his older brother–but Ryokan embraced the label, himself adding the label of dunce as well. He was certainly forgetful, as many anecdotes show: he would go off on an errand and get distracted by flowers or a vista, and forget his purpose. Once he left a guest in his hut to go off to get something from a neighbor and hours later was found by his guest gazing at the moon.

Ryokan was sentimental about birds, flowers, insects, trees, even his begging bowl. His poems show him teary about old friends not visiting, old friends passed, the lonely sounds of animals in the mountains,the drip of rain at his window reminding him of youth, or when he measures the passing years as each season changes. All of these sentiments he committed to poems, regularly taking up brush and paper when prompted by rain, snow, darkness, cold, memory, cheer, or any other provocation.

His eremitism is that of Stonehouse and Hanshan — mentioning that he has the poems of the latter. This eremitism is a pure and simple Zen. Ryokan studied in a monastery and knows the sutras, for example, but he seldom invokes them. He conjures no doctrines or particular points of view. He only takes to scrupulous sitting meditation — plus the right attitude or frame of mind. He quietly dismisses all worldliness, the red dust of society’s commerce and interactions, and enters the stream of the Way. Ryokan acutely feels his solitude, his outright loneliness at times, and is more open about these sentiments than most hermits, but he would not have life any other way because where he is this way represents the totality of this moment, of the season, of the vista from his window, the necessity of the present, undeciphered, unfathomed, that which must be embraced in quietude, even resignation.

A death poem could be Ryokan’s purest sentiment, a brilliant summary in one poem — except that Ryokan did not intend this poem to be a death poem, just another poem:

What will be my legacy?

Flowers in spring,

the cuckoo in summer,

the crimson leaves of autumn.

Ryokan was sensitive to the significance of weather patterns, the shifts from summer to autumn, the shifts from autumn to winter, the return of spring. He interpreted them as a poet, and lived them as a solitary. But he applied Zen insight to everything, and is remembered for his expression of mushin, of “no-mind,” which is exactly how he lived. For Ryokan everyone should live going about with kindness toward others in a state of no-mind thus entering the Way.

Another notable theme, not contrived by Ryokan but certainly observable to his reader, is his profound sense of mujo, impermanence. As mentioned, Ryokan identified himself completely with the Way, but in what does that consist? It is to identify the patterns of the seasons that in turn reveal the cycles of reality, necessity, impermanence and of letting go. Ryokan did not devise a life-style to pursue the Way, only to sit and observe, to take in the lessons, and to accept this process as enlightenment itself.

We do well to do likewise … plus, we have his poetry.

Jung’s psychological types

About a hundred years ago, psychologist Carl Jung issued his seminal essays on psychological types, introducing the now common concepts of “extroversion” and “introversion.” Jung considered the two types not original to himself, suggested, for example, by Goethe’s “systole” and “diastole” observed scientifically in the heartbeat, but also in the seasons, biology, music — what one Goethe editor calls the “interplay of polarities.” Jung applied this familiar idea to human behavior. Though popular audiences reduce extroversion and introversion to personalities, only about 20 percent of the population -— 10 percent on each pole — is exclusively one or the other type. Eighty percent of the population is relatively balanced, able to summon either disposition as needed.

Jung explains that the two types of behavior are not whims or deliberations but very specifically define our relationship to objects in our environment. Such an object may be a person, a landscape, a gathering, even an idea. The extravert defines a group of people as an objet and defines his relationship to it positively, an allure, an attraction, an opportunity, a source of energy, stimulation, and uplift. The extrovert will want to take in the object, make it part of self, merge or immerse with it as a desired part of self. Indeed, the object becomes the self through a subjective or introvert medium deeper than the external display of behavior.

In contrast, the introvert will see the same object, for example, a group of people, as a burden at best, a threat at worse. It is not that the group is objectively menacing, critical, or boring. The object is unnerving, unsettling, threatens the balance and inner tranquility that the introvert prizes, is always seeking to maintain. The object is foreign and inexplicable to the introvert, not intellectually or even socially but at a deep emotional level representing disquiet, uncertainty, threat to integrity, in the sense of wholeness. The object is not recognized as parallel or positive to any of the introvert’s psychological values or disposition. The relationship to the object, in short, is not a relationship, for the introvert rejects any relation, even when “trapped” into being in the presence of the object.

The important point for Jung is the object, yes, but the relationship to the object. The object has an objective status to the 80 percent, and it defines the object by its own characteristics, which is the goal of objectivity. To the extravert, the object is a delight, a lure, a pleasure, a stimuli. The object enters the psyche of the extrovert and is assembled among positive experiences. The object for the extravert, if very highly valued, becomes internalized, part of the self. Thus, while the majority looking at the object will judge its importance by a variety of criteria, the introvert may decide quickly on the positive value of the object, even to the point of wanting to embrace the object as essential. At this point the object becomes part of the self of the extravert, and is treated the way an introvert treats those treasured parts of the self.

How does the introvert treat its preferred objects? When the introvert encounters an object, the introvert can compare and contrast it with objects already within self. For the introvert will intrinsically have subjective preferences, and this subjective ambiance of inner self will apply the same behavioral criterion as does the extrovert. Does this object resonate with my emotional values? Does this object nourish or debilitate my energy. Is the object so multi-faceted that it cannot be judged instinctively? Is this object so complex that deciphering its impact is too much effort, too ambiguous, too elusive? Or is the object a stimulating challenge, an intrigue worth puruit?

Where the extrovert looks for stimulus, the introvert looks for compatibility with measure and restraint. Where the introvert looks for excitement, opportunity, novelty, creativity, the introvert looks for stasis, predictability, innocuousness, inconspicuousness. Experience with objects and emotional states provoked or maintained by objects becomes an automatic response with introverts and extroverts. They alreay know what they like. They are not objective any more. In both cases, objects are elevated to positives or negatives, not considered neutral or passive objects. Objects are quickly forced too be useful or not, to be compatible or not.

Jung’s notion of types is not, therefore, that of the popular view.The popular view wants to push the relationship to objects to an extreme, in order to reveal the inner workings of the introvert or extrovert. This push by popular observers of the types is frustrated by the fact that everyone and not just the types deal with relationships to objects. Inevitably, these objects often confound the average person. Based on a person’s response to an object, the person may have a well-established set of criteria or values but not know how to decide about the object, fear judging it, unable to decide in the definitive way that the introvert or extravert can decide.

Jung’s close study of historical personalities and how their relationships to objects works is both logical and startling. We tend to think of ideas and beliefs as larger than one person, but Jung shows how cultural tendencies that are taken as universals, embraced by common consensus, can change suddenly when the ideas are seen as objects and are elevated by s strong and extrovert personality to the status of real and necessary, an “introvert” function. This application to real historical examples is the subject for a future entry.

Jung identified other spectra besides the extroversion/introversion that is the most familiar “type.” Ultimately, there is no “type,” only our response to objects. Taking a knock-off test like Myers-Briggs will not reveal deep psychology, the unconscious, or even the superficial personality. Reality will consist of managing the subjective and objective, in assigning the environment of each person to social, cultural, and psychological factors, before we can adequately judge the impact of any given object in any given life.

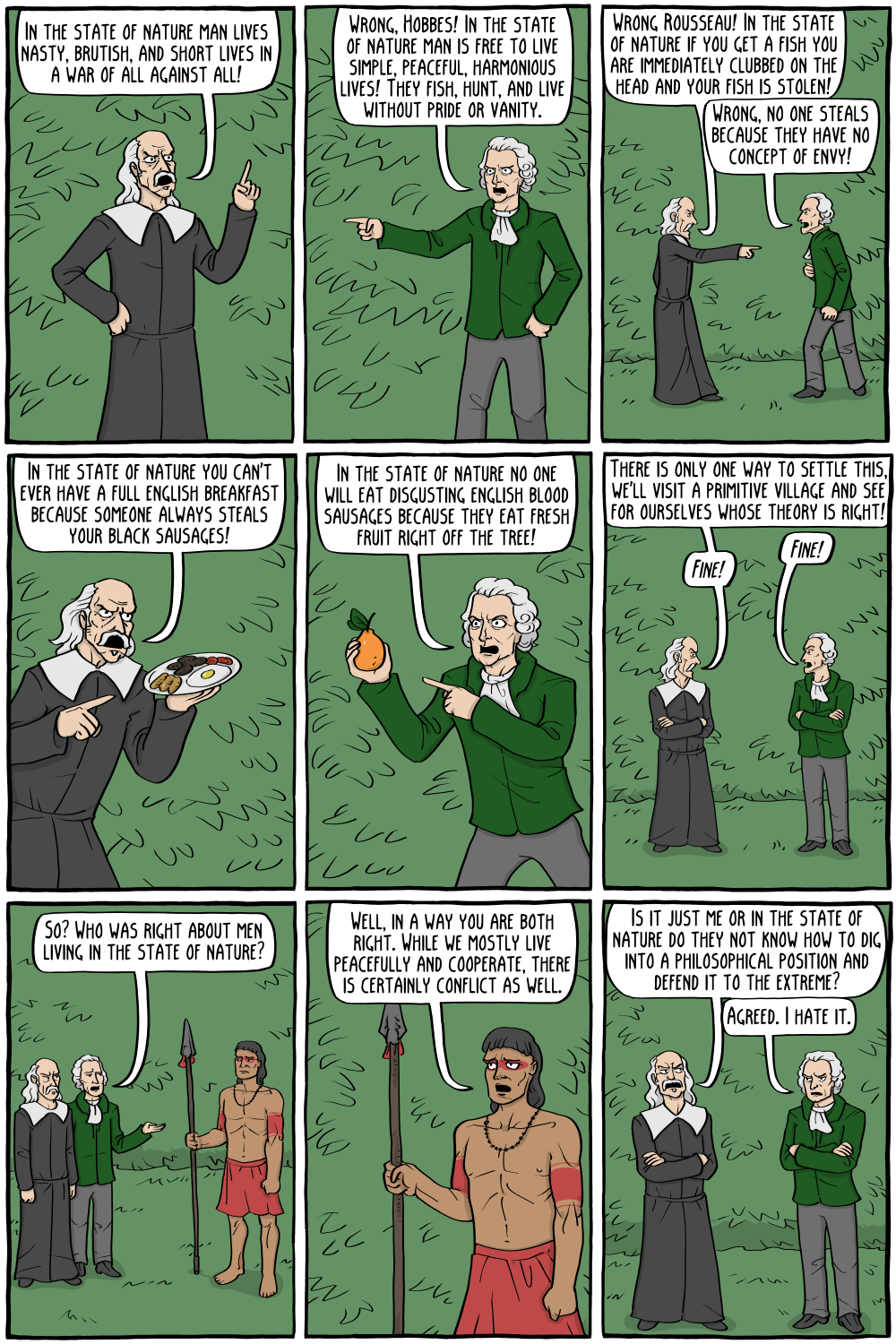

Rousseau, solitary walker

Blame for the devolution of the French Revolution into a reign of terror has often been placed on Jean-Jacques Rousseau, specifically his Social Contract, a structuring of society wherein individual citizens cede part of their autonomy for the “general will.” Rousseau’s general will was conceived by him as a distasteful but necessary concession given what society had become: a Hobbesian structure of exploitation by the rich and powerful versus the dispirited situation of the masses. Rousseau was not an advocate of such a state but a prophet of its probable triumph, given the control over daily life and culture he had already discribed and critiqued in the Discourses.

Rousseau’s early works had already generated resentment and opposition across the ruling elites. His books were proscribed by both political and ecclesiastical authorities. In the nineteenth century, laws against blaphemy, let alone against the ideas of a societal alternative to injustice and oppression suggested by Rousseau, were endemic to Europe.Rousseau not only made enemies but lost friends who renounced him for their own safety. He was hounded from his own native Switzerland (where a mob once descended on his house pelting it with rocks), to France, to England. Rousseau returned to France at the behest of a wealthy sympathizer who promised him protection. He returned to Paris, in old age, where he lived in relative obscurity. He no longer held ambitions to popularize his ideas or persuade others. Instead, Rousseau wrote that he wanted nothing do with people, that everyone had become his enemy, that he would rather embrace solitude than put up with anyone from his past.

These remarks Rousseau wrote in a book intended only for himself: Reveries of a Solitary Walker. He wanted to review how he got to solitude. Still intensely consumed by his universal betrayal, the animosity of everyone, he wanted space to reflect on where he was at thisjunction. Naturally, Rousseau sounds bitter. He writes essays around the theme of taking reflective walks, a usefule device, perhaps. But the walks are not relaxing. On the first walk, taken from Paris to its outskirts (not a suburbia then but to the transition point from city to agriculture and wilderness), a reckless carriage hurdling down on him sends him into a ditch, nearly run over. On another walk he goes through a village cheerfully saluting the gaggle of small children curious about the stranger, but mothers and caregivers quickly scramble to bring the kids indoors, staring suspiciously at the walker. Rousseau imagines that they recognize him: it’s another persaonl affront.

The rest of the reveries of his “walks” are increasingly more resentful and bitter, and the device of “walks” drops away. Rousseau wrote ten of these little essays. His interest in botany, not unlike Thoreau’s and Emily Dickinson’s, is refreshing, and occasionally he makes a philosophical remark to brighten his solitude. But the reveries are dark, often self-pitying, and melancholic. Yet Rousseau believed that human nature was essentially good. It was society and other people who ruined it. Or, as a later Frenchman (Sartre) says in his play No Exit: “Hell is other people.”

Walking

Walking is a natural function. Walking took on a special meaning culturally when it became part of ritual and religion. Walking became a special expression of piety in pilgrimage: the Christian Way of St. James, the hajj of Islam, the Kumbh Mela of Hindu India.

Similarly, ritual postures are performed successively to pursue a regime that approaches piety. These are pronounced in Islam, especially Sufism, and exist to a modest degree in Christianity. The Hindu tradition formalized ritual postures into yoga, where the concept of yoga is both a mental/spiritual discipline and a succession of formal postures performed. A simple manifestation of posture servicing religion or spirituality is the act of sitting in meditation.

Walking is a unique function in the pursuit of wisdom. To walk, to pursue a single “postural” expression repeatedly, not a step or pose but motility itself, with direction and vigor, is flexible, functional, and eminently simple. Sage individuals have incorporated walking into their lives as methods of insight. The examples are many. The Greek philosophers were called peripatetic because they had no fixed abode,thus no fixed posture, intellectually or physically. Atthe same time, they perambulated, walking while teaching. The hermits of ancient China regularly sought out mountains in which to dwell, walking many miles in seeking new homes. What more evocative scene than Lao-tzu, the author of the Tao te ching, walking westward and stopping at a final outpost to share his thoughts with a solicitous sentry there, and then walking onwards, not to be seen again.

In modern times, great figures who consciously walked include Jean-Jacques Rousseau, author of Reveries of a Solitary Walker, Henry David Thoreau, author of “Walking,” but also of the substantial Walden, which includes vignettes of walking, and Hermann Hesse, author of Wandering. A hermit-walker is the narrator of Jean Giono’s The Man Who Planted Trees. All of thee authors and their works address solitude and the solitary life.

Thoreau understands that walking is more than merely a means of transport, from one point of business to another. He prefers sauntering, and notes the interesting derivation of the word sauntering as walking within san terre,literally “holy land.” Walking in nature transforms the land about into an idyll in paradise. It is a conscious means to an intentional end: without carriage, without animal transport, not an equestrian, not a rider, but a walker, a “more ancient and honorable class,” Thoreau notes.

Rousseau, in bitter old age, also took long walks from his city residence in Paris into the countryside, in an era when city’s edge was farmland and nature, not suburbia. Rousseau recorded his thoughts on these long walks, frankly missing details of nature for his own preoccupations, although like Thoreau and Emily Dickinson after him, avid collector of herbs and flowers that attracted his eye, pursuing an amateur’s botantical knowledge in identifying and collecting plants.

Hesse’s fictional Wandering, which reads like nonfiction, is filled with aphorims, romantic reveries neither Rousseau nor Thoreau. Hesse’s incorporation of nature in a philosophy of life is, however, reminiscent and full of depth, where walking, like wandering itself, is a metaphor for making our way through life. And the way, the path, is life itself, unfolding before us.

Thoreau emphatically rejects walking for exercise. Such walking lacks the essential attitude of attentiveness to nature. Thoreau owns that walking in the woods could mean long stretches of time without getting far distant. On the other hand, a villager could walk for exercise without noticing anything in surrounding nature, let alone the resident of our contemporary cities where green spaces are sparse and nature sadly suppressed. But, after all, Thoreau’s essay is titled “Walking, or The Wild” and his signature conclusion is that “all good things are wild and free.”

Under the bridge

A story in the Daily Star (UK) runs with the headline: “Homeless man has lived under noisy dual carriageway ‘like a hermit’ for 11 years.” The item is not unusual for a tabloid, conjuring up another story about a crazy man readers can gloat about with a thump, telling themselves they are glad and pleased not to be that madman. Not that the subject is conscious of some moral purpose or pretense. Or that he isn’t mad.

The item is a reminder of a Japanese Zen story about Tosui (among many sources is Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, compiled by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki, first published in 1957). The story gives a dramatic twist to virtue, strength, mindfullness. Plus, it’s a good story.

An old Zen master [Tosui] had grown weary of instructing monks and announced his retirement. He did not indicate to anyone what he intended to do or where he intended to go, but a novice student pursued him and asked. The master looked dubiously at the young inquirer. The master told him that he was going tolive under a bridge, and with that the master grabbed a few things for his bag and left. The novice followed him, saying “I intend to follow you.” The master looked back, scoffing, and turned to make his way.

After some time the master reached the bridge in the middle of the city, which was crowded with poor and lost souls. The master walked about, surveying the homeless, abandoned, half-crazed, confused, and desperate, but also noticing quiet, pensive, studied faces, some scrutinizing him fearlessly. The novice tagged dutifully behind. At last, the old master found an unoccupied spot and settled his few belongings. The novice sat next to him, conspicuously quiet, his large eyes looking about in a mixture of curiosity and terror. The darkness of evening was descending quickly,and so, too, the chilly air. The master wrapped himself in his old cloak and lay down, telling the novice that he was going to sleep. The novice was still looking around him, wide-eyed, fear etched in his face. Slowly, the scene settled, as men moved to their spots beneath the bridge and became motionless in the dark. The novice noticed that the old master had forgotten to eat. Or did not intend to do so, though the novice felt at one moment keen hunger, another a great nausea.

Hours later, daylight was breaking. The homeless under the bridge began to stir, a few at a time. The old master was among them. The novice slept, exhausted. The master looked at the man next to them. He was not moving, but the old master noticed that the man’s face was trapped in a grimace. The old master came nearer, and realized that the man had died overnight. The novice was stirring and pulling himself to a sitting posture. He was stil very uncomfortable, and still looked around himself warily. The old master noticed. “Ah, you are still here!” he said to the novice.”I was sure you would have returned to the monastery by now.”

The novice smiled wanly, searching the master’s eyes for comfort. “See here,” announced the master. “This fellow here, who slept a few feet from us, is quite dead. We will have to bury him shortly. And look! He has left us a half-eaten bowl of rice, no doubt his unfinished dinner. A bit cold, but here, young novice, let’s have breakfast.”

With that the novice wretched and heaved. “Bah!” said the master angrily. “I told you you were no good for this life. Now, go, back to the monastery with you! Get out! And make sure you tell no one that I am here.” And with that the young novice fled.

URL: https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/homeless-man-lived-under-noisy-22868139

Favorite hermits 4., briefly

Speaking of the benefits of solitude, as in the previous post, a pandemic reading list of Chinese and Japanese hermits is always appropriate — even as pandemic continues, and the relevance of some of our favorite hermits continues to prove perennial. An “Isolation Reading List” from a contributor to the Buddhist magazine Tricycle dates from April 2020. (Other favorites can be added, to be sure.)

The five favorite poets are: 1. Hanshan, 2. Hsieh Ling-yun, 3. Saigyo, 4. Ryokan, 5. Shiwu (Stonehouse).

URL: https://tricycle.org/trikedaily/isolation-reading-list/