What is the vilest stereotype of a hermit? Start with the image of the old loner, secretive, suspicious, furtive. That is what Lance Morrow begins to depict in a short chapter of his Evil, An Investigation (2003), which he indicates is a true story. There is always an easy disposition in the popular mind to portray solitaries as mentally sick, quietly deranged and morbid, but thankfully keeping to themselves. In Morrow’s example, the latter becomes a redeeming virtue, for it keeps the particular man from ever committing a crime. That is what the writer hopes, at least. But we do know that for every solitary like his example there are myriad other men (and women) gliding smoothly or otherwise through the corridors of society and power, with little of the observable clues that would make them clearly what Morrow calls evil.

Disaster

In most Western languages, the word “disaster” comes from the Latin dies aster, meaning “bad star.” According to this primordial view of the universe, calamity is precipitated by the unfavorable alignment of stars and planets. Subconsciously or otherwise, our culture still thinks of nature as irrational and vindictive, sometimes acting to punish for past evil, sometimes presenting omens of more to come. From these ideas it is an easy step to the notion of God using nature or to the dichotomy of nature versus God, with the inevitable question of why God sends or permits evil.

Yet man-made disasters, though incremental, have been and are far more insidious and destructive to humans, sentient beings, and the earth itself. From war and exploitation to destruction of the environment, the bad stars are human. Would media report these man-made disasters in the same way? No, because they occur incrementally, gradually, while popular attention is always seized by the sudden and sensational. Patterns and increments fall below the threshod of the average person’s perception. Slow dissolution and destruction, like time and space, are stretched out over lifetimes. The bad stars sit behind desks and hide behind walls and do not reign in the heavens.

Anchoress of Shere

Little is known of the 14th-century English anchoress Christine Carpenter, but a book and a film have decided on versions of her life and motives.

Anchoress of Shere by Paul L. Moorcraft (2002) shifts between a narrative of medieval events and the chronicle of the psychopathic Catholic priest recreating the history while pursuing his own violent fantasies. The book is published by Poisoned Pen Press but is not a diverting mystery, like a Brother Cadfael or Sister Fidelma. It is a sadistic and masochistic tract. Even from the point of view of the contradictory plot, how can the mad protagonist know anything about spirituality? For that matter, how can a reader learn anything about a medieval anchoress, or the novelist presume to explain anchoritic spirituality?

Being a visual medium, the film Anchoress (1995) can do a little more with an imaginative setting, realistic atmosphere, and characterization. But no comment — not having seen the film. Critics concentrate on the uninspired acting, though the plot seems more plausible. But salaciousness is always the theme of the day. This is not the spirituality of Julian of Norwich or the daily eremitical life addressed by Aelred’s Guide for Anchoresses.

Thankfully, modern minds have done little more to eremitism than these two awful versions.

Moon and sun

At dusk, the full moon is a lantern hung in the trees, the slender pine trees against the sky like black grill-like slivers over the source of light. In a nearby tree I notice a vague and unfamiliar shape. A moment later the shape eerily passes before me in a straight line, in utter silence, and disappears towards the moon: either an owl or a bat.

At dawn, the rising sun, further south than its nocturnal counterpart, tries to etch a like presence, but it is too diffuse and awash with reddish tints that drip everywhere. For a moment the intensity of light is not dissimilar to that of the moon, but only for a moment. Soon the brash sun is stumbling forth, forcing its way onto the stage called sky.

Morning musing

My favorite time of day used to be dusk, when long shadows of twilight suggested finality, reconciliation, the completion of tasks well done or at least assayed. But now I think of morning more favorably: opportunity for beginning anew or reconsidering, for strengthening and adjusting and pondering another time. Sunlight seems more precious now, not to be squandered or curtained away. Birds chirp and wildlife visit. The other night, in the pitch darkness of morning, an owl hooted. In my foolishness, the call was wisdom’s invitation: rise, prepare to salute the sun and the new day. You are granted another gift from the cornucopia of existence, from a vibrant universe that does not want to do without you today.

Art and divinity: Pantocrator

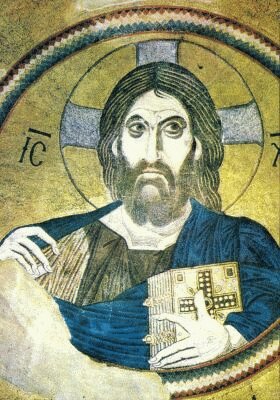

The depiction is standardized throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, almost always called “Christ Pantocrator.” The word “pantocrator” means “ruler of all,” which carries the connotation of the Old Testament Yahweh, the fierce god of Deuteronomy who commands his people to slaughter their enemies, take their women, and destroy their cities. The image of Pantocrator attempts to reconcile the power of Yahweh with the humanity of Jesus, but who will gauge the image a success in that regard? Can they be reconciled?

Orthodox Christian spirituality, which names and depicts this fearsome image, maintains nevertheless the possibility of “divinizing” the self, something the West has never dared to consider or to even propose in its vocabulary. Perhaps we begin to divinize ourselves by reconciling ourselves to the unreconcilable contradiction of the Jesus of the theologians. He did not want to be a king but in this image he is forced to wear the terrifying cloak of Pantocrator.

Hermit Martha, hermit Mary

In a section of his Three Studies in Medieval Religious and Social Thought, Giles Constable considers the persistence of the Martha and Mary dichotomy as it related to daily life and religious vocation. The contrast of the active and the contemplative represented by the Gospel story was used to create conflict between religious orders. But Constable notes that several medieval hermits (Herveus, Helias, Amantius, Wulfric) all refuted the charge of being neither Martha nor Mary. To the hermits, the eremitical life embodied both activity and contemplation.

For the medieval hermit, activity consisted of labor, self-sufficiency, independence of means — which often meant evangelical poverty as a deliberate path that automatically curbed the excesses of Martha. This was the hermits’ retort to the monks living without laboring, without self-sufficiency, and without poverty. The hermits’ lack of formal ritual was a controvery to the orders. But the hermits might contrast it to the monks’ “contemplative” life, which they suggest is actually a life of the luxury of sloth and material comfort, incapable of embodying true contemplation. However, the hermits never went so far as to say this. They wrote nothing, said little. They were more concerned to show action and contemplation with the example of their lives, just as both Martha and Mary simply went about their lives after Jesus had visited them.

Changes II

Much of what we call or observe as change is contrived by culture. It is brought about artificially by those in power and authority, then redefined as inevitable and necessary for society to accept. The manipulation of markets, economic displacement, technology, profit — no events in modern time are progressions like the seasons or cycles of nature. No reading of stars or entrails of victims or discerning of the will of God in human events can justify the rapacity of human agents. Why is war counted as good for gross domestic product? Why is deforestation or getting cancer good for the economy? Because someone profits from destruction and resupplying the tools of destruction. Because changes require economic decisions and thus “stimulate” the economy. What is defined by modern society as good is consumption, but consumption is destruction, Saturn devouring his children, not Kali regenerating the cycle of nature. The solitary should see through the contrivances of society, the fiction of indefinite change as necessary for the common good. The majority of people suffer the more society pursues this sort of “change.” The common good is in that star, forest, flower, and daydream.

Changes

Modern culture has redefined change. Charts assign points to “change events” such as family, job, health, and financial changes. Such changes are redefined as stress. Traditional and spiritual practices related to understanding these life changes are repackaged as “stress management.” But is not change part of a grand and universal cycle? Are not impermanent creatures bound to a cosmic wheel of nature and the universe? Instead of looking in the direction of stress, we must look in the direction of patterns, cycles, and harmonies. Our lives are happier when we fit them to this natural flow, leaving behind (or at least psychologically suspending) the stress that culture wants us to use for measuring the value of our lives.

Art and sagacity

Among the many portraits of sagacity is Rouault’s The Old King. The work can be interpreted as appealing to monarchy or rule, but the tragic expression of the face denies this and reveals the paradox of power. Rouault has many portraits of Christ, and The Old King is one of them, next to portraits of clowns. The Old King embodies the paradox of divinity and human fragility. Jesus did not want to be made a king, yet he has been made a god. Further, one can reflect upon the tragic sense of Plato’s dream of a philosopher-king, a dream that has never come to fruition. One thinks of Marcus Aurelius, the closest exemplar, rather than the naive but reckless Christian kings of medieval Europe that might be suggested with this painting. Or we can think of the fabled Yellow Emperor of China so esteemed by later generations as an ideal, because they never knew him as a historical reality.

Among the many portraits of sagacity is Rouault’s The Old King. The work can be interpreted as appealing to monarchy or rule, but the tragic expression of the face denies this and reveals the paradox of power. Rouault has many portraits of Christ, and The Old King is one of them, next to portraits of clowns. The Old King embodies the paradox of divinity and human fragility. Jesus did not want to be made a king, yet he has been made a god. Further, one can reflect upon the tragic sense of Plato’s dream of a philosopher-king, a dream that has never come to fruition. One thinks of Marcus Aurelius, the closest exemplar, rather than the naive but reckless Christian kings of medieval Europe that might be suggested with this painting. Or we can think of the fabled Yellow Emperor of China so esteemed by later generations as an ideal, because they never knew him as a historical reality.