In the night’s stillness, the moon is small and aloof, its soft light barely sufficient, barely necessary. Still, a strong luminescence reflects from pebbles, rocks, clusters of trees and leaves, a white-surfaced work-table. The eerieness of this textured light combined with a distant reticent moon seems to dissolve night, but not the way sunlight dissolves daytime. The moonlight is enveloping like a fog, with a haunting sense of irretrievability.

Mirror to the self

Plato taught that every person wants happiness no matter how wicked they are because whatever they do they do it believing that it will bring them happiness. Of course, Plato did not know psychology, not even as well as the playwrights and historians of his time. By this standard, everyone desires peace of mind, too, because whatever they do they claim it is for their own good.

Happiness or peace or mind: it is the same error, for our desires, our clingings and graspings, are rationalized as necessary to achieve a state of mental satisfaction or, for that matter, happiness. This realization should be a caution to us. The most important mental function we have is to constantly “check in” with ourselves as to why we do things. We must analyze as bluntly as possible whether what we want is realistic, whether what we say (to ourselves and others) is honest. Fortunately, we don’t have to confess or mumble these secrets to anyone, just keep our own watch on our thoughts. This is, after all, what used to be called “examination of conscience” except that now we are not looking for sins but for habits, assumptions, values, emotions, aspirations, and illusions. Plato’s Socrates is right when he calls the contrast an “unexamined life.” We see this lack of self-knowledge everywhere around us. We must hold a mirror to ourselves, polishing it all the time in order to reflect truly what we need to see.

“Autonomous self-reliance”

Gotama (the Buddha) presented his preference for “setting off alone, without a companion” as a model for all who seriously pursue the path of self-knowledge and enlightenment. Stephen Batchelor calls this the “model of autonomous self-reliance,” and it is certainly familiar to the hermit tradition regardless of culture or era.

In this model, Gotama sent off his disciples not to house themselves in monasteries but to mingle with people as they saw fit or to recluse themselves as they saw fit, but always to function as solitaries. They would share their wisdom with people or build their wisdom in forests and hermitages and the like, but the point was the rejection of institution-building. Here is a clear affinity to the Hindu and Jain sadhu rather than the priestly Brahmin class.

We can see the same model in Jesus when he bids his closest disciples to disperse in no more than pairs, carrying no money or food, only a staff, accepting with gratitude the invitation to enter a house but shaking the dust from themselves when made unwelcome. The disciples of Jesus mingle with the people as they see fit or presumably recluse themselves when they need to do so, but always funtion as solitaries. There is no hint in the Gospels of institutionalizing themselves like the priestly caste, the Pharisees, the equivalent of the Brahmins.

The model of “autonomous self-reliance” is viable to earnest hermits but also to the majority of seekers who value solitude but know that they are bound to live in society.

Ownership

People tend to forget that both Gotama and Jesus were wandering ascetics. They were homeless and deliberately without property. “The birds have their nests, and the foxes their dens,” but not so Jesus or Gotama, and enough evidence suggests that they intended that their disciples should be likewise.

Yet even while householders and we moderns may not find ourselves able to follow the radical example of Gotama and Jesus, we recognize in their poverty and simplicity the truth that ultimately we own nothing, we control nothing, that nothing belongs to us. This is our identity with other beings in the universe, for does a tree or mountain or planet own anything? Even as we use the goods of this world (like a tree uses sunlight and rainfall and nutrients in the soil) we must admit to just temporarily borrowing things and having to give them up in the end. And we know that end, regardless of whatever individual tradition we follow. Are we not reminded facetiously that even the sun will expire in a few billion years?

Our lives should be a reflection on how we go about this “giving up,” little bits at a time, even as we go about our daily lives. Contrast modern culture, media, and self-help books that urge us to maximize our use of worldly goods and experiences, like insatiable gluttons. St. Augustine says somewhere that we should study how to die as much as how to live. Our lives should be a study on how free we can be if we do not cling to things, or at least begin giving things up now.

Raccoon passes

Midmorning and the raccoon is among the plant saucers that serve as water containers for birds. In fact, it stands in one and looks about vacantly. Then it is obvious: the tell-tale limp, and the horrible nasal discharge: rabies or distemper. The raccoon was standing in the water because of fever. Whether distemper or rabies, it is not agitated but it is clearly in its last stages.

A phone call to the wildlife office and they suggest trapping the raccoon under a bin until they arrive. By then the raccoon painfully but with surprising speed left the front of the house and went to the woods east. He found a comfortable spot into which to borrow, under leaves and a canopy of pine needles, and there he lay. I hover nearby, first standing, then sitting on the bin I had dutifully brought. The paralysis of either rabies or distemper eventually spreads up the spine to the brain; perhaps the creature was not going to move again.

In the makeshift burrow, still visible to me when I stand over it, the raccoon wheezes and hacks and shifts restlessly, raising its little head occasionally, then is quiet for a long time, its little back barely lifting with each labored breath. I must have sat an hour, as if in vigil, with many reflections on life and suffering and innocence and futility. I was sure the raccoon was dying. And still the wildlife people don’t show up.

Then, in a burst of energy, the raccoon limps out of the burrow. It wants to go back to the water and heads west. Dutifully, the bin goes over, and a couple of bricks hold it down. The air holes are adequate. It’s over, I guess.

I go inside, guiltily. Half an hour passes, and still no wildlife staff. Going outside to check, the bin seems quiet. Perhaps the raccoon has died or is sleeping. But next to the bin is a hole, the dirt scattered. A flip of the bin and it’s clear: the raccoon has escaped! He had summoned enough energy to elude the supposed sympathies of a human being.

I will probably never see the raccoon again. It did not return to the same burrow. Nor will it trust a human again for the rest of its short life. Rabies transmits to other mammals only if bitten, but distemper is more ravaging, and may affect all the raccoons in the colony. I recalled the Features photos from a year before, the Thatch entries about the antics of the raccoons climbing to the roof, their eagerness for sunflower seeds and their contentment in the front yard.

I called the wildlife staff and told them what had happened. But now I was glad they had not shown up. What would have been the creature’s fate? Trapped, caged, flung about like so much dross, a long and frightening truck ride, far from familiar habitat, then a cold antiseptic metallic lab with a single overhanging bright light: what a way to die! This creature deserved to be free, to be undisturbed, to navigate the bardo in its own way. Is that not what we all should want for ourselves, for all sentient beings?

Art and melancholy

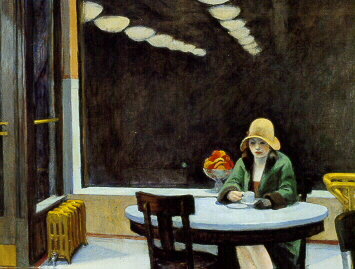

The city as society’s agent abandons its denizens as night abandons light, as easily as it discards the aged and children and solitaries. The melancholy of urban night intensifies the melancholy of the city as the individual’s own pretenses to contentment are stripped away by the betrayal of autonomy that society represents. Edward Hopper, the twentieth-century American realist painter, captures this mood in his 1927 The Automat, made famous by a 1990’s TIME magazine cover.

The city as society’s agent abandons its denizens as night abandons light, as easily as it discards the aged and children and solitaries. The melancholy of urban night intensifies the melancholy of the city as the individual’s own pretenses to contentment are stripped away by the betrayal of autonomy that society represents. Edward Hopper, the twentieth-century American realist painter, captures this mood in his 1927 The Automat, made famous by a 1990’s TIME magazine cover.

Moon spill

A brilliant full moon is casting cold clear light straight through the curtains and onto the bare floor. I look up, startled and shivering, thinking: What a mess to clean up!

But then I awaken. Bolting up in the dark I see that the floor is clean. No light has spilled anywhere. The moon has since moved westward in the night sky and the angle of its light no longer touches the floor. I sigh in relief, thinking: Nothing to clean. Not one speck of dust.

Joinville on hermits

In his Chronicle of the Crusade of St. Louis, the thirteenth-fourteenth century writer Joinville mentions an incident refering to hermits. On his party’s arrival on the Greek island of Lampedousa, he relates:

We found an ancient hermitage in the rocks and the garden that the hermits who dwelt there had made: olives, figs, vines and other trees. The stream from the fountain ran through the garden.

In this idyllic place, they found a cave, and in it two bodies, long decomposed, hands on breasts and laid out to face east. Clearly these were occupants of the hermitage. The party returned to the ship and discovered that one of their mariners was missing.

The master of the ship thought the sailor had remained on the island in order to be a hermit. Whereupon the king’s master sergeant left three bags of biscuit on the shore, so that the mariner might find them, and subsist on them.

Disasters II

In a passage somewhere in Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, the protagonist, who is a Chinese farmer, looks at his fields and reflects on an impeding famine. The river is quickly rising and will flood the lands so that nothing can be grown for a year or more. But the protagonist does not think of this disaster as evil. Every seven or eight years nature brings a flood — or a drought — and the people suffer, but nature is not an evil. This thought is coherent with an Eastern philosophy, but in the West it was the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 that shook philosophical foundations. Where many Christians saw the disaster as an omen, Voltaire wrote

Will you say: ‘This is result of eternal laws

Directing the acts of a free and good God!’ …

Did Lisbon, which is no more, have more vices

Than London and Paris immersed in their pleasures?

Lisbon is destroyed, and they dance in Paris!

A wise course for the solitary is to accept nature as a profound mystery, but not tantamount to God, and not an instrument of divinity. Nature is a play of vast forces, and consciousness is a thin, ethereal and tenuous element in the universe not likely to premeditate or presume.

Zen moment

I look around

proudly

housework done

everything clean

then, I frown

it won’t last

already

dust on the mirror