The structures and morals presented by traditional religions, especially the three scriptural religions of the West, have a clear historical and cultural basis. By the time the historical religions address many of the essential issues, it is too late — human beings have developed particular instincts, behaviors and values that are already set long before the religions conceive of values and abstractions that can affect social existence. Neurology and anthropology now contribute research that only further demonstrates what has always been anticipated by sage individuals who did not bind themselves to the tribal and cultural circumscriptions of the historical religions of their day. That they could borrow from them, reform them, or transform them, even as firm and long-lived institutions, was at most an adventitious sally.

The human brain developed primordial behaviors that predate formal history. The first such stage is amply demonstrated by the paleolithic, characterized by sheer survival interests: food, shelter, hunting, territoriality, and reproduction, a set of behaviors dominated by the amygdala, a stage appropriately called reptilian in its instictiveness. The era of the instinctive brain saw the expansion of human beings over Africa and Europe and beyond. The era brought the whosesale extermination by humans of entire species such as the wooly mammath and saber-toothed tiger, destroyed by rapacious hunting. This behavior also created the rudiments of society, for as humans sought larger and more numerous prey they came to realize that cooperation in numbers led to more effective hunting. Thus was nurtured familiar social behaviors, hierarchies, power displays, and tribalisms.

The second stage of brain development is the limbic or emotional, which provided sensations, responses, and feelings to human experience. The more primitive responses were within the realm of fear as human gauged situations and became capable of responding to them, chiefly as fight or flight. Thus the experience of the paleolithic (fight not flight) is transmuted into the reflectiveness of, for example, what is witnessed in the Lausaux cave paintings, where we see humans clearly engaged in the activities of the Paleolithic but now becoming aware of the patterns in animal life, movement, and migration, and suggesting that these patterns evoke emotions. From the limbic stage, memory rituals evolve to capture the emotional experiences, engendered by a desire to give greater meaning to the animal hunt, to put the animal and the human into a larger context evoking feeling. Second stage sensibility tempers the later Indo-European and Semitic animal sacrifice rituals into religious expressions.

The third stage of brain development is the most decisive: the neo-mammalian complex, which in turn developed four distinct areas (and functions), these functions further enabling existing evolutionary potentials to finally find a conscious channel of control and use. The five senses, for example, could now be consciously applied and used, as opposed to being merely passive and receptive functions without self-consciousness, without even the tentative self-consciousness of the second stage hunter. The developed neocortex included four brain lobes and their attendant functions: the occipital (visual), the perietal (spatial), the temporal (sound, speech, voice), and the frontal (integrative and coordinating the other three). This development provided human beings the ability to assign context and continuity to all human experience and memory.

With the fourth stage we are led to the holistic being identified today as a person.

The fourth stage of brain development was the sophistication of the prefrontal cortex, which allows for the immediate processing and assigning of meaning for retention of all the experiences initially processed in the third stage. Development of the prefrontal cortex provides the essential regulation of fear as an emotion, to the entire “fight or flight” syndrome. The prefrontal cortex does this by providing context to events, by providing emotional feedback and reason (or at least sensibility) to address events and context, and, importantly, to compare experiences, judge them, and make plans for addressing them in the here and now and into the future. In terms of brain development, stages one and two form the clearest distinctions of behavior, while three and four emerge logically and are available for social application.

Historically, brain development provides tools and functions, and only hints at socially functional and ultimately culturally and morally viable behaviors. Use of the brain to optimially develop beahviors and ethics is an elusive pursuit, and has never been of predominance in the institutional and cultural history of the major civilizations, where stage one behaviors around power, hierarchy, and control, enhanced by late stages for incorporating reason and persuasion, make the stage one behavior more formidable and lethal. War, aggression, and violence have been the hallmark of society.

The brain’s development has ben frustrated at every cultural turn by the rejection of late stage behavior in favor of stage one behavior orcestrated by elites utilizing late stage behavior manipulatively. One need only glance at the scriptures of ancients, from Hebrews to Greeks to Etruscans to Persians, from Indo-Europeans to later Semites, to witness the hunter stage extended into civilization and urban life and institutions, often with the clever use of late stage behavior. (And the same can be said of modern society.)

Thhe input of religious thought — itself a product of the same given cultures — is therefore always too late chronologically in mitigating this process of social and political behvior. Either the religion ends up collaborating with stage one behavior or underestimating the entrenchment of society in stage one behavior. One looks to more authentic later stage behaviors prompting the human ability to specialize, plan, appreciate, create, and aspire only to find these behaviors compromised and corrupted by the institutions that suppressed these behaviors and thoughts in favor of the powerful.

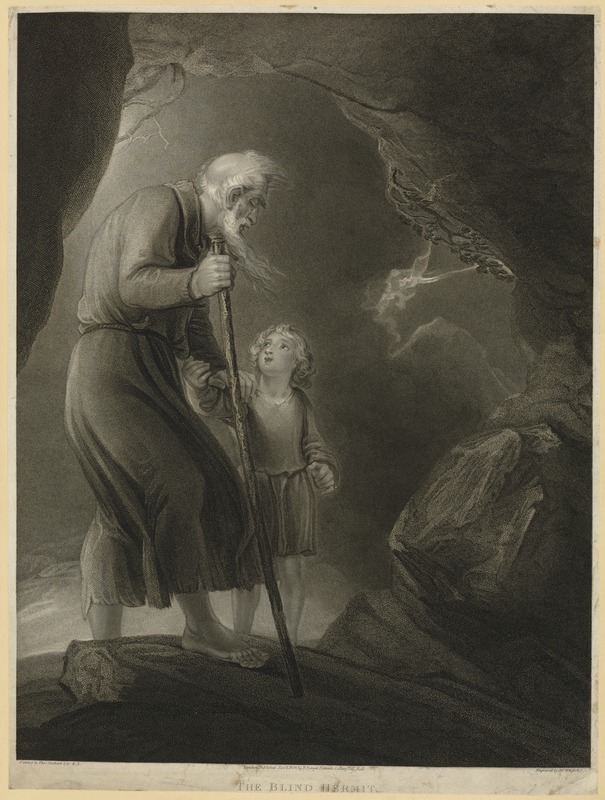

Inevitably the exceptional sages and the eremitic personalities of antiquity and not the mainstream religious or philosophical thinkers were to provide intellectual breakthroughs and social models alternative to their contemporaries and their cultural circumstances — in India, China, Japan, and tangentially in East Asia and Europe.