The 20th-century Japanese photographer Masehisa Fukase’s book of haunting photographs published as Karasu or Ravens reasserted a traditional view of ravens as symbol of darkness and death. Fukase’s photographs of ravens in various grains of black and white evoke at once a sense of unease, repulsion, pity, and despair — as intended. The 1980’s English translation of the work as The Solitude of Ravens further captured the sense of alienation, strangeness, the status of pariah, outcast, of deformity and repulsion.

|

|

|

|

In ancient Celtic and Norse mythology, the raven fits this symbolism. The ravens’ apparent maleficence derived from their habits as scavengers consuming carrion, especially on gory battlefields. In Irish mythology, the war-goddess Morrigan haunted the battlefields in the form of a raven. The war-drenched Norse similarly filled their mythology with ravens as devices. Though modern populaces have largely sanitized their witnessing of the horrors of war even while wars rage on, the symbolism of ravens lingers.

But ought not the raven’s alleged maleficence be attributable as much to the architects of war and not to opportune birds with an evolutionary niche? Are not eagles, like vultures, likewise scavengers? The presence of ravens anywhere intensifies the mystery of human behavior and the darkness inhabited by the unconscious mind.

In literary terms, Edgar Allen Poe’s famous poem “The Raven” served to extend the macabre association of ravens with death. But Poe mingled death with the quest for wisdom and equanimity. The raven symbolized knowledge in ancient Greek culture, and the raven in the poet’s chamber alights on a bust of Athena, goddess of knowledge. Understanding the raven is to grasp an insight into existence.

In contrast, however, is the raven depicted in Western Christianity. In this tradition the raven is presented in a positive light, associated with saints. Here the raven’s submission to the will of God despite its disagreeable habits is an expression of redemption. The stories of ravens in Christian tradition indicate that however objectionable the behavior of any creature, it can ultimately pursue what is good. In doing so, the reader or listener cannot but admit the benignity of nature and creation.

Here are some depictions of ravens in Christian tradition:

In the Old Testament, ravens feed the prophet and hermit Elijah with “bread and meat” where there was no other source of sustenance.

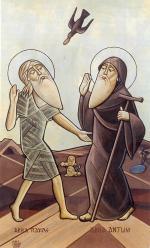

In St. Jerome’s story of Anthony meeting the famous desert hermit Paul a raven is featured prominently. It fulfills God’s purpose as a sign of holiness. Paul greets his visitor thusly:

“Behold the man whom yon have sought with so much toil, his limbs decayed with age, his gray hairs unkempt. You see before you a man who were long will be dust. But love endures all things. Tell me therefore, I pray you, how fares the human race? Are new homes springing up in the ancient cities? What government directs the world? Are there still some remaining for the demons to carry away by their delusions?”

Thus conversing they noticed with wonder a raven which had settled on the bough of a tree, and was then flying gently down till it came and laid a whole loaf of bread before them. They were astonished, and when it had gone, “See,” said Paul, “the Lord truly loving, truly merciful, has sent us a meal. For the last sixty years I have always received half a loaf: but at your coming Christ has doubled his soldier’s rations.

|

|

|

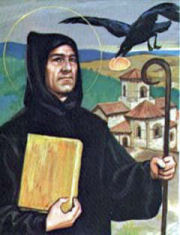

According to tradition, a raven regularly visited St. Benedict of Nursia to receive a bit of bread. One day, Benedict was given poisoned bread by a jealous monk. He implored the raven to take it away and conceal it. The raven did so, not eating it, and returned shortly thereafter for its regular morsel.

The 9th century hermit St. Meinrad, who regularly fed ravens, was murdered by thieves. Ravens pursued the murderers into the forest, their loud caws alerting the villagers to come and apprehend the men. (The Benedictine monastery of Einsiedeln, associated with Meinrad, used ravens in its coat of arms).

These Christian stories of ravens may not have reversed popular perceptions of ravens but have two virtues: 1) they point to a sense of benignity in creation, and 2) in each instance, ravens are associated positively with the solitary and with places of solitude.

How can the sense of benignity towards ravens exemplified by these tales outweigh the image of the raven associated with the oppression of war and destruction that is so intense in our consciousness, a restless despair, hopelessness, and unease?

Fukase precisely taps this uneasiness. It is not necessary to be on a battlefield to feel this way. Life is a battlefield as far as the subconscious is concerned. We only need a negative symbol to provoke the unease. The ravens in warfare, ancient or modern, provoke it. Even the ravens going about their lives, as Fukase shows.

Or do we dare go one step further? Is creation plagued by humans the same way that ravens plague our dreams? Solitude in Fukase is both the condition of ravens but also the projection of our uneasiness.

We cannot picture the hermit, regardless of tradition, turning his back on any creature. On the contrary, we can imagine the hermit, in solitude, identifying with the raven — shunned, provoking disgust, reduced to ignominy. The hermit stories strive to transcend our human fears, even as we acknowledge the entrenched causes of human misery emanating not from ravens but from the human heart.