In 17th century Japan, a middling middle-aged poet and scholar moved to a hermit hut. Matsuo Kinsaku had disciples, hangers-on who aspired to fame for his own sake. They bought him a banana-tree for his new quarters.

A banana tree in Japan is an anomaly, having been imported from south China or other warmer climates. The banana tree dies with freezes. In warm months it splays out large leaves with a great green sheen. The poet came to like its great leaves, vulnerable to tearing in the wind but wonderful to listen to the sounds of rain falling on those same leaves.

A banana plant in autumn winds —

I listen to the drops of rain

Fall into a basin at night.

Usually the banana of any variety requires a year of stable temperatures in order to fruit, but in Japan the banana would have died every winter, even late autumn.

When the banana suffers freezing temperatures, its leaves turn brown like overdone leafy vegetables, and at night its leaves curl up like a dead spider. Then the leaves turn black, and its watery trunk can be knocked over with a common garden tool, and that is the end of it. On the surface. But like a flower bulb, the roots will generate a new plant in spring, and by summer, the great splay of leaves can be enjoyed again.

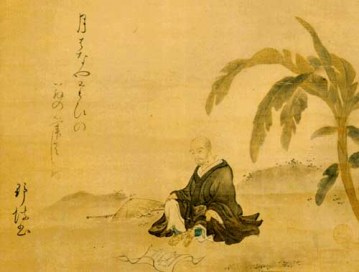

The poet was so enamored of the symbolism and the appearance and the sound that he called himself after the banana, which in Japanese is basho. The poet, of course, was Basho, and his hermit hut was basho-an, the “banana hermitage.” There would be successive huts, as Basho’s poetic skills improved and he took to wandering Japan and seeking out shrines and colorful temples, plodding in the footsteps of the 12th-century poet Saigyo.

Fittingly, a famous portrait of Basho includes a picture of a banana tree.