The physical fields of great austerities have been the desert and the mountains. Both physical contexts remove society and the ego but in different ways, through different metaphors, so to speak. The desert as physical emptiness, associated with dryness, heat, thirst, overbearing brightness, horizonalism, sparsity of living beings. Mountains connote coldness, snow, water, darkness, verticality, a profusion of living beings on the scale of ascent. Neither setting is habitable to the average person. Both represent metaphors of emptiness, forms of transcendence. Both settings have presented their near-inhabitants with religious and spiritual settings for austerities.

Shugendo is the Japanese asceticism of mountains, derived in part from Shinto’s assignment of sacred places in nature, with the mountain as dwelling of spiritual beings, plus the image of transcendence. Shugenda evolved from a mingling of Shinto and esoteric Buddhism, plus a degree of philosophical Taoism. As with Tibetan Buddhism, mountain life conjures a special relationship to natural objects and spirits, as if the heights and the separation from the valleys and flat lands below automatically elevates the person to a new level of spiritual aspiration.

Because of the physical austerities of mountain life, and the disciplinary practices equated to martial training, those who sought out its rigors in Japan were attracted to the warrior life: yamabushi and samuri. While desert hermits have used the vocabulary of combat against demons, their discipline is largely a mental exercise that then overcomes physical pain or discomfort.

In contrast, mountain asceticism in Japan extended to a whole class of male adventurers, soldiers, penitents, and strength-builders not necessarily imbued by religion — or, rather, carving out a martial religiosity akin to eternal combat against a panoply of gods and demons. Such is the evolution of many natural disciplines in East Asia.

The physical austerities may have come first, evolving into sedentary mental exercises later. For example, hatha yoga, the discipline of India’s Brahmins, the religious elite of Hinduism, may have preceded mental and philosophical training paralleling, supplementing, or even coming later. Until this evolution, ritual and mythology would substitute for philosophy and spirituality.

Another example is the evolution of Qigong into Tai chi chuan and on into advanced martial arts specialties. (There is no equivalent in the West. The Greek Olympics did not engender the later schools of philosophy.) An evolved Shintoism redirected martial impulses to a contemplation of nature: trees, rivers, mountains. An evolved Buddhism (Tendai, Shingon) redirected these impulses to discipline, transcendence, a denial of ego. The resulting Shugendo has remained the preserve of male asceticism, with a great deal of ritualism and a minimal emphasis on intellectualism.

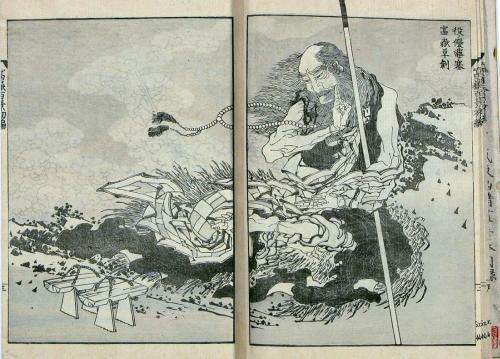

Shugendo is dominated by the image of Enno Gyoja, a 7th century historical figure whom legend transformed into a “founder.” The very name means “En the ascetic.” According to legend, Enno was exiled for trespassing on a mountain in order to pursue religious practice, but every night he flew to the favored mountain, defying his exile. Enno is closely associated, at least by the 19th century artist Hokusai, with the sacred Mount Fuji, appearing as its patron in the artist’s renowned “One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji.

In Hokusai’s modern but spiritualized portrait, Enno Gyoja is depicted as a powerful and self-disciplined man, a capable ascetic, neither god nor warrior, a hermit or holy man renouncing the world and probably any pretensions to supernatural powers. Without the legendary material surrounding the Shugendo founder, however, perhaps the mountains would not have attracted what the scholar Paul Swanson has enumerated as “ascetics, including unofficial monks, peripatetic holy men (hijiri), pilgrimage guides, blink musicians, exorcists, hermits, diviners, and wandering holy men.”