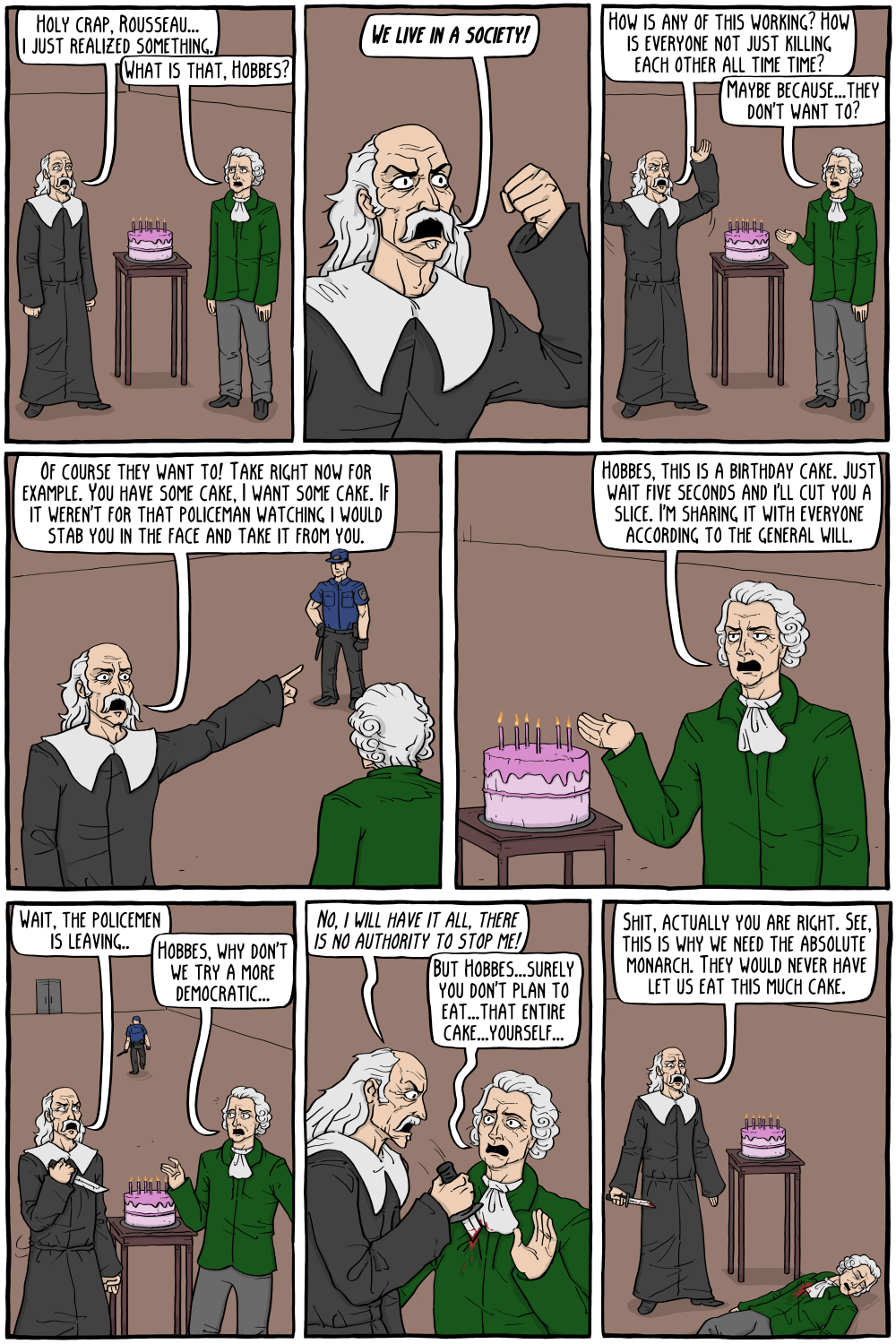

A favorite website Existential Comics presents in a nutshell the clash of the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). By assuming a violent and degraded human nature, Hobbes can pretend to lament summoning authoritarianism as a necessity, while at the same time presenting himself as a staunch ally of the noble-minded state. The very reality of a society persuades Hobbes to suppress human nature, human collectivity, human autonomy.

In contrast, Rousseau affirms that society, already controlled by authoritarian structures, has bludgeoned human nature, that original expression of conviviality, copoperation, and well-being, destroyed its original benignity, and replaced it with the structures that Hobbes thought indispensible. The structures Rousseau would cast off were exactly the structures Hobbes would elevate. Society with its control of the individual from cradle to schooling to livelihood, was to Rousseau an inimical force, a corrupting force. Rousseau applied his principles to every field of soceity, from educatipon, to religion, to economics, and science. He paid for his unorthodox (for the time) beliefs, shunned and hunted by all of their representatives. Eventually Rousseau retired and wrote his reflections as a selection of thoughts, not unlike famous French predecessors (such as Pascal). The Reveries of a Solitary Walker make useful reading for the solitary who needs the examplesf history to understand the course of timem to appreciate the lessons of a lifetime of struggle. But bitterness, not optimism, characterizes Rousseau’s last writings. The authoritarian premises of Hobbes eventually came to influence not only the contemporary empires but statescraft in the Western world ever since.

URL: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/525