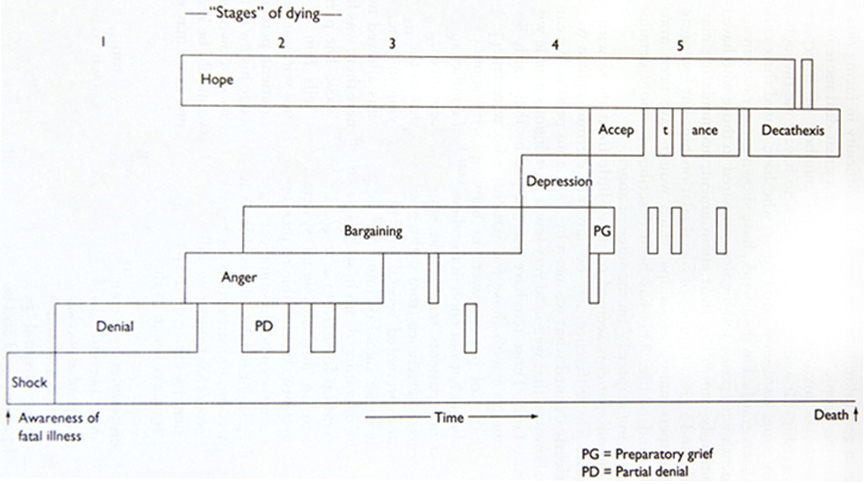

Swiss-born psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (1926-2004) defined five mental or behavioral stages of dying in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. The stages are:

- Denial and isolation

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

The stages were later extrapolated to grief in general. Opponents argued that the stages are not necessarily ordered, depending on the subject, and not necessarily experienced at all in situations where social environment is healthy and individuals are resilient. But the objections come late compared to Kubler-Ross’ work in the fifties and sixties when death, dying, and grief were still experienced by most Americans (those are the subjects she interviewed) in a traditional fashion. Medical personnel was aloof and hospitals were themselves intended to be a last stage for dying patients. Kubler-Ross recounts her childhood in Switzerland and the forms of dying centered in family and village life, the absence of medical technology and hospitals, and the centrality of religious and cultural expression — none of which are constructive factors today, with the larger exception of the hospice movement that Kubler-Ross inspired.

Kubler-Ross notes that hope of recovery was consistently high, even to the end, not only in religious-minded patients but in firmly non-religious. Perhaps it was culture-based, personality-dependent, or simply a survival mechanism. Otherwise, psychology and personality may alone have formed the attitudes of those harboring degrees of anger and resentment. Kubler-Ross’ gentle methods of eliciting a consciousness of these feelings in her patients shows that, indeed, she was aware of variables in individual temperament and resilience.

In retrospect, depression is not as dominant a stage as one might guess. Deriving grief from depression, in turn, suggests a backward application of depression in dying. While real, depression and grief are nevertheless experienced very subjectively. Not surprisingly, they early were targets of the medical and pharmaceutical industries to which Kubler-Ross referred negatively and which preempt the dying process decisively today.

The dying process best culminates in voluntary and conscious decathexis, the withdrawal from people, objects, environments. One might apply the term philosophically in order to approximate the eremitical and sage traditions that have always suggested that life is a process of dying, and that withdrawal and simplicity best nourish this course.

Later in life, Kubler-Ross took a serious interest in near-death studies, tangential but somewhat more speculative, to be sure, versus the psychology of dying. In meditative traditions, the phenomenology of near-death experience is parallel to the pursuit of esoteric powers, to be looked upon with suspicion as a distraction from the true goal of living, and dying.

Less noticed but effective in On Death and Dying is how Kubler-Ross links poetic lines from Rabindranath Tagore to the various attitudes and mindsets typical in the emotional life and in the dying process. This poetic context enriches the somewhat clinical observations in the book, which are, after all, largely transcripts of dying people’s feelings. By developing this poetic and philosophical sense of life and nature, death and dying, the question of resilience and environment can give way to a sensibility that is whole and complete, as should be the dying process itself.

- Denial and isolation.

“Man barricades against himself.” (Stray Birds, 79) - Anger.

“We read the world wrong and say that it deceives us.” (Stray Birds, 75) - Bargaining.

“The woodcutter’s axe begged for its handle from the tree. The tree gave it.” (Stray Birds, 71) - Depression.

“The world rushes on over the strings of the lingering heart making the music of sadness.” (Stray Birds, 44) - Acceptance.

“I have got my leave, Bid me farewell, my brothers! I bow to you all and take my departure.

Here I give back the keys of my door — and I give up all claims to my house, I only ask for last kind words from you.

We were neighbours for long, but I received more than I could give. Now the day has dawned and the lamp that lit my dark corner is out. A summons has come and I am ready for my journey.” (Gitanjali, 93)