Music is the art of collecting narrative sounds to achieve a desired sensibility. Music has a primordial function because sound precedes other human senses. We are blind before birth and require adjustment of sight even in the hours and days after birth. We cannot comprehend what we touch if our eyes are closed but merely guess at texture. Smell is significantly reduced in human beings compared to most animals. But sound, even when not revealing its source, seems to persuade attention, so that even in the womb, sound has an effect on human development.

Identifying why certain sounds are soothing or relaxing plunges us into an anthropology. For example, waves on a beach may echo the regularity of a mother’s heartbeat in the womb and the regularity of swishing fluids in that primordial chamber of safety. The sound of birdsong signals the absence of predators, and , therefore, sources of stress. We are startled by sudden loud sounds like thunder, gunshot, explosions: these are echoes of predators in the underbrush or unsafe perches in branches or rocks.

Music has attempted to create atmospheres of serenity but the imitation of nature is always short of the real thing. The urgency to relieve stress is itself a revelation of the psychological unsustainability of crowded places. The sound of vehicles and rush of noises disturbs our primordial ability to find a refuge of naturalness. The ultimate failure of music to achieve this alternative vision led John Cage to embrace the noise as itself modern music — an unsatisfactory intellectualization. New Age music comes close to consciously trying to reproduce a human project of serenity. To be creative, however, music must embrace as well a philosophical point of view that is compatible with our deepest sensibilities.

The real challenge is to create music (or sound) that, as Schopenhauer would put it, can exist even if there were no world, no one listening to it. That is, if no one heard it, could it still be an echo of reality? This question initially suggests Cage’s direction for a solution but goes beyond, positing a universe without human intervention and taking the sounds of the universe as music. Recordings of radio waves from the stars are usually rather dull listening, but that is because the sounds have no will, no intentionality. What the artist does is find a way of adding intentionality, or rather, ambiance, that will make the music resonate with a human sensibility.

Ambient and space music would approximate this method, except that the sensible component is usually interpreted and rectifies the course of bare sounds. Dark sounds conjure fear; cloud sounds suggest optimism. The composer is still manipulating the listener, or seeking out those who agree.

Music-making cannot be disengaged from human will, but can be used to present philosophies of life projecting from the emotions stirred by music. The idea would be not to try to baldly reproduce nature sounds but to stimulate emotions which in turn would give the listener a non-intellectualized basis for a philosophy of life. Successful music (in the ear of the beholder) would be that music that best satisfies the given philosophy of life.

A good example, perhaps, might be music that evokes sadness, grief, or melancholy. Five classical pieces come to mind:

- Albinioni: Adagio

- Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6, 4th movement

- Mahler: Symphony No. 5, 4th movement

- Barber: Adagio for Strings

- Khachaturian: Gayne Ballet Suite, no. 4

Bach showed early in the history of classical music that a work’s foundation in certain mathematical patterns could evoke particular emotions. While the above classical works are famous for evoking certain emotions, the subtleties of works such as Bach’s “Art of Fugue” show that an awareness of complexities can draw out a more sustainable work of art. The five pieces above are usually isolated from the composer’s whole work in order to deliberately provoke rather than provide — provoke a linear emotion rather than provide a context for reflection on life. But that is not the fault of the composers, only of modern audiences too busy to hear out the entire works.

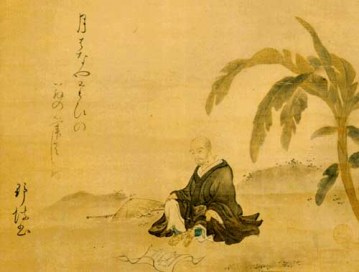

The most representative shakuhachi music of Japan is truly philosophical music in that it assembles sounds to evoke nature and to express a philosophical mood without targeting a linear or single emotion. The mathematical line is as simple as Bach, but its philosophical rooting in Zen clears away extraneous cultural and musical accretions. At the same time, a deepening experience of the music — as with meditation practice — deepens the philosophical suggestibility of the music. This does not mean that the listener must be a philosopher. Successful music will allow the emotional ambiance to percolate through the mind that is already disposed to constructing a philosophy, or at least intuiting one.

Thus, as a counterpart to the Western works that evoke sadness, grief, or melancholy may be placed the famous “Kyorei” (“Empty Bell”). Casual listeners will identify it with melancholy. But this famous work does not so much evoke emotion as evoke an ambiance in which to reflect on the nature of things. In this sense, Schopenhauer’s concept of music as a kind of echo of Ideas when all else is gone is well achieved in “Kyorei.”