Michel Foucault notes, in his book Madness and Civilization, that the medieval depiction of the desert hermit of early Christianity was one of being assailed by external demons. The view conformed to the writings about the hermits. These were temptations requiring enormous effort to combat, but external temptations nevertheless.

However, in the late Middle Ages, with the end of leprosy as an underlying social fear and the closing of all leprosaria all over Europe, a transformation took place transferring the external disease to a spiritual and internal state of folly or madness. This is an oversimplification, of course; Foucault is more specific.

This transformation was applied to depictions of the desert hermits as well. As Foucault states: “In the fifteenth century the gryllos, image of human madness, becomes one of the preferred figures in the countless Temptations.”

The Temptations are artistic representations of a theme, namely the temptations of the desert hermits. Historically they had depicted (especially in literature) a devil or demon that, however terrifying, was nevertheless a limited if fantastic and separate beast (the customary horns, tail, and smoke). But the gryllos is a hybrid of human and animal, as if the human being was now possessed by a demon solely because of being tempted.

This represented a significant social and psychological change, not to say theological.

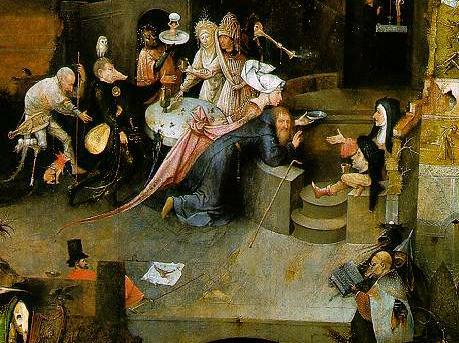

What assails the hermit’s tranquility is not objects of desire, but these hermetic, demented forms which have risen from a dream, and remain silent and furtive on the surface of a world. In the Lisbon Temptation, facing Saint Anthony sits one of these figures born of madness, of its solitude, of its penitence, of its privations; a wan smile lights this bodiless face, the pure presence of anxiety in the form of an agile grimace.

The Lisbon Temptation is the famous tryptych “Temptation of St. Anthony” by the Hieronymus Bosch preserved in Lisbon, Portugal (http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/b/bosch/90anthon/ and http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/bosch/tempt-ant/). The figure in the central panel of the tryptych is a kneeling St. Anthony.

As Nicholas Pioch (or an editor) of the WebMuseum succinctly puts it:

The central panel of this triptych illustrates the kneeling figure of St Anthony being tormented by devils. These include a man with a thistle for a head, and a fish that is half gondola. Bizarre and singular as such images seem to us, many would have been familiar to Bosch’s contemporaries because they relate to Flemish proverbs and religious terminology. What is so extraordinary is that these imaginary creatures are painted with utter conviction, as though they truly existed. He has invested each bizarre or outlandish creation with the same obvious realism as the naturalistic animal and human elements. His nightmarish images seem to possess an inexplicable surrealistic power.

Foucault continues:

Now it is exactly this nightmare silhouette that is at once the subject and object of the temptation; it is this figure which fascinates the gaze of the ascetic — both are prisoners of a kind of mirror interrogation, which remains unanswered in a silence inhabited only by the monstrous swarm that surrounds them. The gryllos no longer recalls man, by its satiritic form, to his spiritual vocation forgotten in the folly of desire. It is madness become Temptation; all it embodies of the impossible, the fantastic, the inhuman, all that suggests the unnatural, the writhing, of an insane presence on the earth’s surface — all this is precisely what gives the gryollos its strange power. The freedom, however frightening, of his dreams, the hallucinations of his madness, have more power of attraction for fifteenth-century man than the desirable reality of the flesh.

Foucault’s interpretation, like that of the classic Johan Huizinga’s The Waning of the Middle Ages years before, suggests the cause of the end of eremitism as the same as what ended the Middle Ages: the end of a reasonable spirituality. Even while the hermit was an eccentric figure practicing a radical simplicity, he was throughout the Middle Ages an “awesome” religious symbol revered for his spiritual power if not his freedom. But the dissolution of the spiritual is, as Foucault shows, the dissolution of reason (or reasonableness) and the ascent of madness in culture. Even if we do not ascribe to a given spirituality, we will have to account for its social function sooner or later.

The creatures depicted in church art as gryllos (half human, half fantastic animal) and the hybrid monsters of Bosch’s semi-religious paintings are projections of the psychology of a dying culture, a culture riddled with fear and madness.

Fear and madness are the plagues of a culture that cannot tolerate solitude, silence, simplicity, harmony with nature, nor eremitism. For in these depictions of society the times are too far gone, purpose, meaning, and a reasonable norm are lost. The millenarianism of this era presented the coming end of the world not suggested by anything real but by the behavior of the people themselves, conjuring fear, terror, and madness. The end of the world is suggested not by anything real but because the minds and hearts of the people require it.