My favorite time of day used to be dusk, when long shadows of twilight suggested finality, reconciliation, the completion of tasks well done or at least assayed. But now I think of morning more favorably: opportunity for beginning anew or reconsidering, for strengthening and adjusting and pondering another time. Sunlight seems more precious now, not to be squandered or curtained away. Birds chirp and wildlife visit. The other night, in the pitch darkness of morning, an owl hooted. In my foolishness, the call was wisdom’s invitation: rise, prepare to salute the sun and the new day. You are granted another gift from the cornucopia of existence, from a vibrant universe that does not want to do without you today.

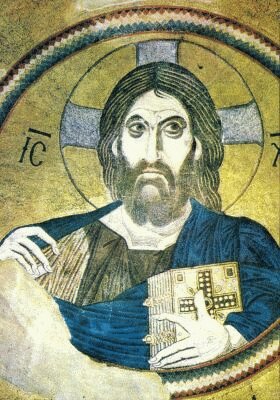

Art and divinity: Pantocrator

The depiction is standardized throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, almost always called “Christ Pantocrator.” The word “pantocrator” means “ruler of all,” which carries the connotation of the Old Testament Yahweh, the fierce god of Deuteronomy who commands his people to slaughter their enemies, take their women, and destroy their cities. The image of Pantocrator attempts to reconcile the power of Yahweh with the humanity of Jesus, but who will gauge the image a success in that regard? Can they be reconciled?

Orthodox Christian spirituality, which names and depicts this fearsome image, maintains nevertheless the possibility of “divinizing” the self, something the West has never dared to consider or to even propose in its vocabulary. Perhaps we begin to divinize ourselves by reconciling ourselves to the unreconcilable contradiction of the Jesus of the theologians. He did not want to be a king but in this image he is forced to wear the terrifying cloak of Pantocrator.

Hermit Martha, hermit Mary

In a section of his Three Studies in Medieval Religious and Social Thought, Giles Constable considers the persistence of the Martha and Mary dichotomy as it related to daily life and religious vocation. The contrast of the active and the contemplative represented by the Gospel story was used to create conflict between religious orders. But Constable notes that several medieval hermits (Herveus, Helias, Amantius, Wulfric) all refuted the charge of being neither Martha nor Mary. To the hermits, the eremitical life embodied both activity and contemplation.

For the medieval hermit, activity consisted of labor, self-sufficiency, independence of means — which often meant evangelical poverty as a deliberate path that automatically curbed the excesses of Martha. This was the hermits’ retort to the monks living without laboring, without self-sufficiency, and without poverty. The hermits’ lack of formal ritual was a controvery to the orders. But the hermits might contrast it to the monks’ “contemplative” life, which they suggest is actually a life of the luxury of sloth and material comfort, incapable of embodying true contemplation. However, the hermits never went so far as to say this. They wrote nothing, said little. They were more concerned to show action and contemplation with the example of their lives, just as both Martha and Mary simply went about their lives after Jesus had visited them.

Changes II

Much of what we call or observe as change is contrived by culture. It is brought about artificially by those in power and authority, then redefined as inevitable and necessary for society to accept. The manipulation of markets, economic displacement, technology, profit — no events in modern time are progressions like the seasons or cycles of nature. No reading of stars or entrails of victims or discerning of the will of God in human events can justify the rapacity of human agents. Why is war counted as good for gross domestic product? Why is deforestation or getting cancer good for the economy? Because someone profits from destruction and resupplying the tools of destruction. Because changes require economic decisions and thus “stimulate” the economy. What is defined by modern society as good is consumption, but consumption is destruction, Saturn devouring his children, not Kali regenerating the cycle of nature. The solitary should see through the contrivances of society, the fiction of indefinite change as necessary for the common good. The majority of people suffer the more society pursues this sort of “change.” The common good is in that star, forest, flower, and daydream.

Changes

Modern culture has redefined change. Charts assign points to “change events” such as family, job, health, and financial changes. Such changes are redefined as stress. Traditional and spiritual practices related to understanding these life changes are repackaged as “stress management.” But is not change part of a grand and universal cycle? Are not impermanent creatures bound to a cosmic wheel of nature and the universe? Instead of looking in the direction of stress, we must look in the direction of patterns, cycles, and harmonies. Our lives are happier when we fit them to this natural flow, leaving behind (or at least psychologically suspending) the stress that culture wants us to use for measuring the value of our lives.

Art and sagacity

Among the many portraits of sagacity is Rouault’s The Old King. The work can be interpreted as appealing to monarchy or rule, but the tragic expression of the face denies this and reveals the paradox of power. Rouault has many portraits of Christ, and The Old King is one of them, next to portraits of clowns. The Old King embodies the paradox of divinity and human fragility. Jesus did not want to be made a king, yet he has been made a god. Further, one can reflect upon the tragic sense of Plato’s dream of a philosopher-king, a dream that has never come to fruition. One thinks of Marcus Aurelius, the closest exemplar, rather than the naive but reckless Christian kings of medieval Europe that might be suggested with this painting. Or we can think of the fabled Yellow Emperor of China so esteemed by later generations as an ideal, because they never knew him as a historical reality.

Among the many portraits of sagacity is Rouault’s The Old King. The work can be interpreted as appealing to monarchy or rule, but the tragic expression of the face denies this and reveals the paradox of power. Rouault has many portraits of Christ, and The Old King is one of them, next to portraits of clowns. The Old King embodies the paradox of divinity and human fragility. Jesus did not want to be made a king, yet he has been made a god. Further, one can reflect upon the tragic sense of Plato’s dream of a philosopher-king, a dream that has never come to fruition. One thinks of Marcus Aurelius, the closest exemplar, rather than the naive but reckless Christian kings of medieval Europe that might be suggested with this painting. Or we can think of the fabled Yellow Emperor of China so esteemed by later generations as an ideal, because they never knew him as a historical reality.

Hermits and ponds

Hermits are of two types, like ponds.

One type of pond is fed from below, from deep sources of living water constantly refreshing the whole from within. This pond is stable, not changeable. It exists in harmony with its environment, welcomes visitors and vistas of all sorts, alone and in silence at the end of the day.

The second type of pond is fed almost imperceptibly by an upland stream and by rain gentle or strong. The stream and rain mingle with receptive waters that invigorate and bring life and strength. Also almost imperceptibly, a stream trickles away from the pond, downstream, beyond the vision of any pond visitor, which nourishes new ponds and rivulets and streams unseen from the forest clearing, and yet the pond is not diminished thereby. The downstream rivulet joins a brook and then a river, and the river goes on to the sea.

Art and divinity

Art invariably falls short of conveying the true content of divinity and sagacity and instead portrays religion. Renaissance cherubs, the severe Velazquez, the romantic Dore and Blake, the naive American Hicks — all fall short of conveying a sense of mystery or other-worldliness. Modern pious art assumes foreknowledge of scripture or doctrine to convey meaning. Eastern depictions of the Buddha try to portray serenity (except the bizarre Hotei) but the deities are not always benign, as in Tibetan and Japanese traditions. Simple but endearing are Hindu portraits of blue-skinned Krishna with Radha in a forest setting (and there are Western counterparts) where the viewer feels like an intruder who has seen god and is embarrassed, like the apostle of Jesus at the Transfiguration who blurts out that it is good to be here and what do I do now.

Art invariably falls short of conveying the true content of divinity and sagacity and instead portrays religion. Renaissance cherubs, the severe Velazquez, the romantic Dore and Blake, the naive American Hicks — all fall short of conveying a sense of mystery or other-worldliness. Modern pious art assumes foreknowledge of scripture or doctrine to convey meaning. Eastern depictions of the Buddha try to portray serenity (except the bizarre Hotei) but the deities are not always benign, as in Tibetan and Japanese traditions. Simple but endearing are Hindu portraits of blue-skinned Krishna with Radha in a forest setting (and there are Western counterparts) where the viewer feels like an intruder who has seen god and is embarrassed, like the apostle of Jesus at the Transfiguration who blurts out that it is good to be here and what do I do now.

Nature and eremitism

As soon as we complain about the caprices and hardships of nature, we exchange nature for human compulsion. From tempest, drought, mudslide, flood and extremes of temperature, the complaints accelerate to the unyielding earth, the unproductive, earth, the earth ripe for exploiting. And so follows civilization’s course: mining, logging, draining, filling, dumping, runoff, chemical agriculture, pollution. Because these actions require organization, money, and motive, soon concentration of power and authority are compelling not only nature but people to change, alter, adapt, renounce, resign themselves, give up simpler lives and patterns of living. From a harmonious relationship with nature to an antagonistic one, from a relative individuality for all to a collectivity for most — this is the long-term result of our complaints against nature.

This is the economic and social history of most of the world, the core of what is called “development.” No wonder ancient peoples from Chinese to Native Americans were loath to disturb mountains or change the course of rivers or hew forests when they were believed to be occupied by supernatural beings. No such restraint hinders moderns. From nature and the solitary to domination of both nature and solitaries.

It is not a matter of living in wilderness. Early hermits could afford to; modern hermits are more often urban dwellers. But as the natural world is assaulted mercilessly by moderns, a big piece of that eremitism is assaulted, too, by the arrogance of power and the demand for renouncing values precious to the individual, values not merely symbolized by but actively represented by nature and its cycles. All of us — but especially the solitary — must monitor our relationship to the natural world in order to recover the purest sense of harmony with universe and self.

Unamuno on compassion

Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno extends the concept of compassion to all living beings, just as he extends consciousness to all living things. This he links to heightening our sense of imagination, not the capacity for fantasy but for empathy and solidarity with the beings of the universe.

I feel the pain of animals, and the pain of a tree when one of its branches is being cut off, and I feel it most when my imagination is alive, for the imagination is the faculty of intuition, of inward vision.