A theory of linear succession or progress has been the premise of Western philosophy of history from the beginning of the Christian era and on through today. In the earlier form, taken from biblical sources, the line went from creation to fall to redemption to apocalypse: a straight-forward line exemplified by Augustine’s City of God but nascent in all the thinking of the era.

With the Renaissance and Enlightenment, the same point of view is merely secularized, and progress is recast as the evolving of reason, knowledge, discovery, and technological advancement. In the 19th century, Hegel established the framework for a philosophy of progress, and Darwin’s theory of evolution provided a scientific confirmation, especially for the nascent sociology of the time.

But one of the representative writings on the subject, The Idea of Progress by the British historian J. B. Bury, argues that the theory of progress was not possible until the 17th century — not in antiquity, the Middle Ages, nor even in the Renaissance, for three reasons: 1) the view that Greece and Rome had attained the apex of civilization, 2) a lack of acknowledgment of the value of mundane life and its contribution to society, and 3) the lack of a separation between science and philosophy which would free science for its revolutionary breakthroughs.

Hence, Bury would not link the Christian view to a formal theory of progress, nor to Hegel, probably, but to concrete material conditions resulting from the application of post-17th century thought. However, when this theory of progress is contrasted with an alternative such as the Eastern cyclical view or Nietzschean recurrence does it become clear that the theory of progress is distinctly Western, nor merely Christian, scientific, or modern.

The optimism of the West in the continued evolution of society on principles of social and technological progress is basic to Western thought, a faith in rational principles leading to universal improvements, to a best of possible worlds. But the pragmatic theory of progress is functionally contrived by those few who would benefit from the extension of the instruments and institutional structures of progress (economic, financial, political, military, educational, etc.). The average person is expected to accept the notion that society can undergo constant evolution and progress so long as that innate force within history (Spirit, Reason, Science, the “market”) is allowed to be interpreted by the authorities, much like the ancient Roman augurs.

Every once in a while, this acceptance is gainsaid in a particular part of the world, but like a natural seismic eruption or the cycle of tidal ebb and flow, conditions return to where they were, only with new faces replacing the old ones.

Only with the 20th century has faith in the theory of progress been shattered in the minds of many intellectuals, though the majority of the people stubbornly adhere to the augurs of progress. World War I had an enormous impact on a generation of writers, artists, and thinkers, but their work has been viewed by critics (under the rubric of “the academy”) as a subjective expression of mere stress, angst, and the hothouse behavior that results when a person is placed under unnerving conditions.

A theory of progress, decorum, and complementarianism (the view that creative efforts should be expressions of the social-political paradigm, what in the Soviet Union was called social realism) persists in media and popular expression. The coverage selected and the criticism applied has the function of keeping within bounds what the masses consume, what they must consume in order to maintain allegiance to the present paradigm of institutions and beliefs. Underlying these beliefs must be a theory of progress, implicit in the notion that security, order, and well-being are granted by power from above and not sought for or achieved by independent individual effort.

Progress can only be a product of individual consciousness defining health and well-being. No sage has ever advocated consulting the institutions of his age for wisdom but recommended plumbing the mind or heart within to derive direction. Only after the death of sages is the message seized by others for their aggrandizement, made to be a theory of power and domination, and set forth to undermine the spirit of the orginal sage, which always preferred individual effort and a philosophy of solitude and benevolence.

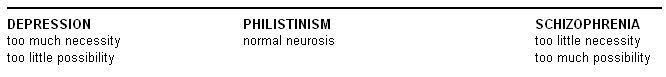

Solitude is inimical to power, shuns power, seeks its own progress. A progress that is an illusion, enhancing the few and fooling the masses, is for the solitary the opposite of progress, for it does not consult nature or quiet the mind in order to begin reconsturcting the self. But the theory of progress is an old device masking power, and concealing what the 20th century creative souls — and those brave 19th century figures like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche — unmasked as lies about human nature.

What is the alternative to progress for the grand institutions of today? It is a devolution to simplicity, to individuals and small social units, to natural industry and exchange, to a relationship to nature based on value and not exploitation or power. The alternative to progress is a devolution of artificial wealth, privilege, and legitimacy.

The “decline of the West” (to cite Spengler’s title) means not only the decline of the theory of progress but the decline of the artificial social and economic conditions that have propped up institutions and circles of wealth and power based on belief in that theory. Here is a beginning point for anyone who has not connected the experience of the 20th century “Age of Anxiety” with the present devolution of global systems of power. Here is the beginning point for a philosophy of solitude based on a realization that progress is a chimera, a fog that suppresses mind, spirit, and body.