Scientists say that immortality is a projection of the animal instinct for survival. This is a reductionism, inevitably more complex than this bald statement, for it does not account for consciousness and its mental products. A better approach might be that of Krishnamurti, although it, too, is brief and leaves out many things.

J. Krishnamurti argues that our relations with our environment, from early one, form the self. All of this data from environment, society, and culture, constitute the self, down to the symbols and language we use to think and communicate, to the externals of food, clothing, and beliefs. All of this data constitutes our consciousness, and everyone “tries to immortalize the product of environment; that thing which is the result of the environment we try to make eternal.”

This data is not consciousness but our consciousness of a self, an “I.” Krishnamurti elaborates:

You are continually seeking immortality for this “I.” In other words, falsehood tries to become the real, the eternal. When you understand the significance of the environment, there is no reaction and, therefore, no conflict between the reaction, that is, between what we call the “I” and the creator of the reaction, which is the environment. So this seeking for immortality, this craving to be certain, to be lasting, is called the process of evolution, the process of acquiring truth or God or the understanding of life.

Krishnamurti’s premise is that the “I” or self is a collection of impressions and reactions, but that directly examined it has no existence. Or, rather, nothing that we need assume would perpetuate itself. If we assume that this “I” must respond and react and engage its environment, the result is conflict, struggle, and inevitable suffering. On a larger scale, the elusive “I” creates institutions and collective bodies that will function as projections of the self to enshrine the symbols, rituals, and mores deemed necessary to the preservation of the self and its attachments.

Do not think this struggle between the self and the environment, which you call the true struggle, is true. Isn’t there a struggle taking place in each only of you between yourself and your environment, your surroundings, your husband, your wife, your child, your neighbor, your society, your political organizations? Is there not a constant battle going on? You consider that battle necessary in order to help you to realize happiness, truth, immortality, or ecstasy. To put it differently: “What you consider to be the truth is but self-consciousness, the “I,” which is all the time trying to become immortal, and the environment, which I say is the continual movement of the false. This movement of the false becomes your ever-changing environment, which is called progress, evolution.

At this point, Kirshnamurti goes on to discuss the self, but an important point is made here, that immortality is not simply an instinct goine bad but is a reaction to the human struggle with environment, with the alienation or separation that we feel from our environment. That this environment is always changing, always in flux, is absorbed by our consciousness as a condition of self. This flux is manifested in anything dealing with our environment, with others, society, and culture. We are on a carousel of time, as the popular song puts it, but only because we insist on monitoring and being on top of the flux.

So, while human beings elaborate the sense of immortality primarily in religious terms, it is not exclusively so. Everyone, of every shade of belief, elaborates this sense by fight the stream of time and change, by seeking to grasp the environment and controlling it to one’s own profit.

The path suggested by Krishnamurti is a philosophical one, but many who are not philosophical attempt to resolve the dilemma of “I” through creativity. Creativity is at the heart of projection of self. We devise ways of distinguishing what we think is truly creative from the artificial, the synthetic, the contrived. This is the making of values.

Immortality can first be distinguished from survival. We know that we don’t need to be creative in order to survive, or do much more than engage in society’s assigned path for us, whatever that may seem to be. Survival is largely taken care of by society and others. We are inevitably and inextricably tied up with one another, so that we partake of whatever we need for physical survival and elect whatever we think we need for psychological survival. The latter category is when we intersect with the contrived aspects of society, especially entertainment, superfluous consumer desires, use of wealth to pursue success, profit, war.

Yet contrivances do not disturb but build the “I” or ego. Once we have failed to distinguish the contrived from the creative, the false path to immortality is etched upon us, except that the path is a finite and eartly one that merely perpetuates the self and maintains it from reflection.

Creativity must be something extra, therefore, supremely unnecessary to survival or socialization but a resolution, or at least a transcendence, of conflict, something sublime or extrapolated even beyond the guarantees of survival and immortality, certainly beyond the ethos of contrived social entertainments. Even the skeptical scientist pursues creativity.

We can catalog the methods by which human beings extrapolate the survival instinct, but soon see the instinct wane, and other factors of sociability enter and take a larger and more elective role. Ultimately, individuals can submerge themselves in the contrivances of others, in the social relations that even passive observation offers. A routine of labor, housing, eating, socializing, and entertainment is ostensibly the equivalent of animal survival, but it is so heavily dependent on social networks for its character that instinct is transformed into a pleasure principle. At that point, individuality is subsumed into the mass, manipulated by the few holding power or notoriety.

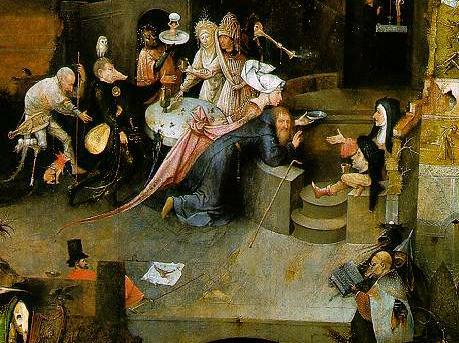

The word “notoriety” originally referred merely to the known, the talked about, but eventually came to have a negative connotation, as in “notorious.” Similarly, “celebrity” originally referred to the status of being known to the many. The transformation of these concepts in modern time points to the expansion of society and the presentation of the powerful and their victims to the public for moral lessons. The contriving of celebrities to be celebrated and the notorious to be execrated is as much a product of how culture empowers itself and perpetuates its power over individuals. What is more of a divergence to the individual than to monitor the doings of packaged issues and concerns that are here today and replaced with a new and equally distracting set tomorrow?

Krishnamurti extends the fabric of social immortality to religion as a social contrivance as much as to modern entertainment with its mind-numbing function of guaranteeing the passing to time without pain or suffering. The search for a savior is the search for a guarantor of immortality, but also the search for one who will celebrate and corroborate the self, the “I” and its contents. It is only a matter of degrees between the mechanisms society creates in order to oth affirm immortality (of a sort) and deny it as sufficient in this lifetime.

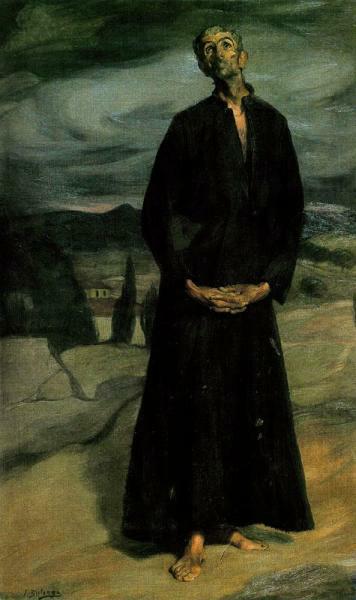

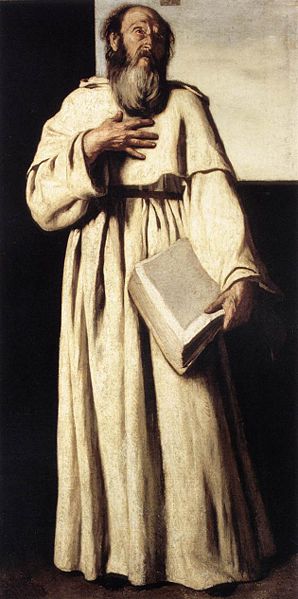

The characteristics of celebrity and notoriety are exactly the opposite of the hermit’s. It is not that the hermit lacks creativity. The celebrity and the notorious are not necessarily more creative than anyone else, only that they are made to channel that creativity to the interests of mass society. The truly creative are seldom noticed or outright anonymous, circumscribed by the time, place, and the extension of their egos. The hermit is not projecting himself or herself in order to fulfill an animal instinct. Indeed, the hermit dissipates instinct by reclusing from society and from the “being known in the world.” Regardless of how narrow the world of the hermit, it is, as the Japanese Zen poet put it, “a universe.”

The hermit’s response to the world is not self-denial. Calls to serve humanity or utilize one’s skills or reach one’s potential are siren calls from society to put the individual to work on its behalf. Working for the world is the opposite of creativity. Creativity is the opposite of instinct. Creativity transcends immortality.

The hermit experiences an unconscious recognition that the mind and heart are destined for other than instinct and survival, other than the flattery of self and ego. This otherness means other than the paths of the world, other than the expectations of society. This sublime realization is what comforts the hermit in knowing that the wild chase of humanity for survival, for perpetuation, for the assertion of “values” is vain at every level, doomed to be thwarted by the very products of society and culture.

Nature is the only guide, not society and culture, for even when civilization carries, like a vessel, the creative efforts of sages past, it also carries the malevolent elements of human consciousness made social. The biblical parable of the wheat and tares (weeds), wherein it is impossible to separate the two because removing the weeds will damage the wheat, is certainly the experience of any gardener or farmer who understands natural methods. Yet the parable only makes more obvious the need to begin the process early and methodically, for it is a necessary process to safeguard the fruit of the field, the fruit of the heart and mind. The weeds flourish because they, too, have similar needs as the wheat for nourishment, sun, water, soil. So does everyone. But the great mass of humanity will hoard the nutrients and choke out the good fruit — such is society and the individual who knows the ways of the world and would pursue another way. The mass of people will choke out the intuitive and creativty within them to chase after the world and its profeered immortality, its mechanism of transference with regard to celebrities and the notorious.

The hermit must dissemble to get along in society, but once within his or her cell, room, flat, house — within the privacy of the self not shaped by the world — creativity, conviviality with nature and the universe, the quest for virtual identity with both flux and transcendencecan begin.

The solitary’s way is of humility not hubris, disengagement not contention, self-effacement not celebrity or notoriety. The hermit rushes to nature and the pattern of the universe, not the contrivances of society and culture ready-made to dull the individual, to fill the individual with illusions, to distract self from introspection. Noise, pleasure, false creativity, the desire to perpetuate the debris of environment, as Krishnamurti might call it, have always been shunned by solitaries. The hermit’s way is modest, reclusive, with barely a footprint as to where the hermit has tread.

Happy the man, whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air

In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread,

Whose flocks supply him with attire;

Whose trees in summer yield him shade,

In winter fire.

Blest, who can unconcern`dly find

Hours, days, and years, slide soft away

In health of body, peace of mind,

Quiet by day.

Sound sleep by night; study and ease

Together mix`d, sweet recreation,

And innocence, which most does please

With meditation.

Thus let me live, unseen, unknown;

Thus unlamented let me die;

Steal from the world, and not a stone

Tell where I lie.

Solitude, by Alexander Pope