The history of major religions reveals a pattern of attempting independence from the negative accretions of a previous religion — but falling short.

Two major sets of world religions confirm this pattern: Christianity considers itself the successor of Judaism. Buddhism succeeded Hinduism without intentionally its successor, which it is not. But the original religions are the seedbed and do not disappear. The primordial psychology of the seedbed religion lingers in the new religion. The result is a later extrapolation of the new religion into new cultures, new temperaments, new political and cultural realities. Soon, it, too, either splinters or extends the original “successor” further.

In the new religions, the psychologies differ enough from the seedbed, from the geographic and mental terrain. The trajectories are too dissimilar, the historical circumstances too different — a break occurs.

In the process, Buddhism (but not Jaina) eventually departs India. Ostensibly, Buddhism is not hobbled by Hinduism in its earliest manifestation of simplicity in Theravadan form, where it takes on the character of the South Asian culture and personality. The structure of deities and the cosmogony of beings, however, remains dependent upon Hinduism, as does popularizations of Buddhism. Likewise, while Buddhism rejects the class system or asama of Hinduism, it retains karma and multiple lives. The stories of the past lives of the Buddha resonate with the atmosphere of Hinduism, presenting a seamless psychological succession that in historical terms was not to be fulfilled.

Mahayana, the great splinter of Buddhism, departs Hindu India for Tibet, China, Japan, and Korea, all under many nuanced differences from the Theravadan “lesser vehicle.” Theravada transforms the Buddha’s sangha into a priestly class or ascetic arhat society. The extended cosmogony adds new stages of moral state to the hierarchy of hell-bound, hungry ghosts, and the brutish, adding — of particular importance — the state of Bodhisattva as an angelic accompaniment to the human struggle for salvation.

Christianity (but not Islam) eventually departs the Holy Land. Christianity is hobbled by Judaism in the core definition of deity and being, unable or unwilling to reject the character and concept of Yahweh for a new spirituality. But the God of the Judaic Old Testament having monopolized all notions of theologizing, remains fixed and immovable in Christianity. The compromise of Trinity, especially in the Holy Spirit, becomes itself a source of later disruption and sectarian conflict. The universalism of moral values in Jesus, and the historical (versus the priestly) mission of Jesus cannot sustain itself against the more narrow project of universalizing Yahweh, a project inspired by the uniformity of Roman imperial authority.

The early Christian desert hermits, like the mystics that would appear in medieval and later Europe, attest to the absence of a consistent ethics in the project of philosophizing from religion, of establishing the values within the marrow of society versus the priestly project of hierarchy and sacramentalism, a distinction made by Taoism and in part by later-stage Buddhism, specifically Zen.

As with the historical Buddha, Jesus the founder may not have intended to create a new religion, and did not live long enough to elaborate a spiritual path that also intersects with historical and social circumstances. Before long, the infrastructure of the old and narrow origins in Judaism engulfed the personality of the historical Jesus. The ecclesia of his earliest followers, like the sangha of the Buddha’s, was narrowed from the universal community to the hierarchy of priestly religion and hierarchical moral states. Buddhism in the South had six moral states, Mahayana ten. Christianity needed only three: heaven, purgatory, and hell. Protestantism reduced the stages to two: heaven and hell. The Christian-inspired secular philosophers such as transcendentalists and unitarians, reduced it to one: universal salvation.

Thus the cycle of several thousand years — when Judaism, Shinto, Jaina, and most primordial religions, including the ancient Greek, conceived of death as a vague stage of lingering spirit, a beingness destined to fade and disappear except for memory of the living — spun off into mixtures of folklore and theology. Only the mystics would try to bridge the primordial and the historical with a transcendent insight.

Islam escaped the institution of strict priestly hierarchies and social structures, accepting the cultural wisdom of elders and their consent and input in social and ethical affairs of the community. But not unlike the other scriptural religions of the West, Islam passed from the intuitive vision of a “founder” to a disintegration into sectarianism and authority, with the Sufi mystics preserving the purity of values and religious attitude transcendent but innate within the community. Origins in a bellicose cultural psychology, entwined with geopolitics, overcame the purest conception of Islam — as it did Judaism and Christianity. The legacy broods over systems of ethics and belief even now.

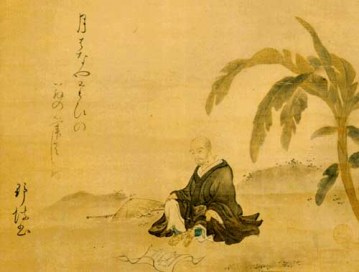

Of the major religions, Taoism thrived in independence from these historical declines through the tradition of its philosophy. Taoism was a philosophical religion, a spiritual philosophy. The character of Taoism reflects the very soil and circumstances of its origins, the historical situation which occasionally, if tragically, is reproduced again and again. An appreciation of Taoism calls for penetrating into these historical circumstances, placing oneself within the philosophical debates of the Warring States era of ancient China — a microcosm of every era everywhere, especially our modern era. The conjunction of thought afforded by Taoism gives meaning to the work of many lives and voices of the past, regardless of the circumstances or traditions into which the sage or saint was born.

The potential of the other world religions to become philosophies or “spiritualities” is undermined by history and authority, by the primordial strife for power endemic in all societies, especially our modern ones, incapable of rescuing basic understandings. A metaphor from nature is apropos: When striking thinkers, sages, and saints, emerge from a world religion, it is not the seed but the flower or fruit we witness. The flower or fruit is the evolved seed that has survived bad accretions of cultural and social soil. The flower or fruit has taken the better part of the seedbed and at last found sunlight, water, and air, those essential elements of nature that the seedbed, with its tumble of primitive instincts and brute willfulness, could not offer.