Richard Proenneke, Alaskan Wilderness Hermit

Richard Proenneke (1916-2003)

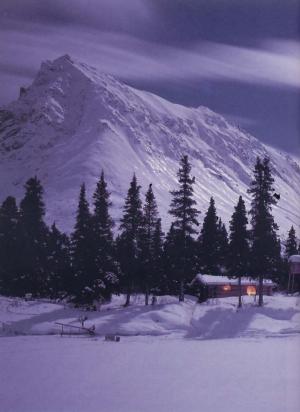

spent 30 years of solitude in the remote Twin Peaks region of Alaska,

beginning in 1968. Proenneke was eminently qualified for his goal. Considered by observers a "mechanical genius,"

an amatuer naturalist and meticulous observer, he was eventually employed by

the National Park Service for his knowledge and wilderness experience.

Proenneke was by no means an anti-social recluse fleeing civilization.

He maintained a circle of friends and associates, was "an inveterate letter writer and diarist," and

extended his positive attitude toward self, nature, and other people.

Richard Proenneke (1916-2003)

spent 30 years of solitude in the remote Twin Peaks region of Alaska,

beginning in 1968. Proenneke was eminently qualified for his goal. Considered by observers a "mechanical genius,"

an amatuer naturalist and meticulous observer, he was eventually employed by

the National Park Service for his knowledge and wilderness experience.

Proenneke was by no means an anti-social recluse fleeing civilization.

He maintained a circle of friends and associates, was "an inveterate letter writer and diarist," and

extended his positive attitude toward self, nature, and other people.

Proenneke became known through books and videos. Sam Keith reconstructed Proenneke's first-year journal and published it in 1973. John Branson edited the 1974-80 cabin years, representing Proenneke's years of public recognition. Bob Swerer assembled Proenneke's vast collection of photographs and films into several popular videos. Keith's version captures the style and rhythm of the days and nights, of nature, work, and solitude. Despite editing, Branson's version at 500 pages challenges the casual reader. These years of increaased social involvement and Parks Service dealings sacrifice the pristine solitude of the early years.

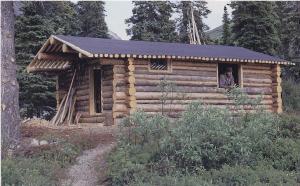

Proenneke immersed himself in the details of whatever tasks presented themselves. He built his log cabin from hand tools, explored the mountains and rivers on foot and canoe, meticulously observed animal behavior and habitat, and recorded his thoughts with a sympathetic attachment to the wilderness. At the same time, he regularly corresponded with family and friends, and increased his personal contacts during visits away from the cabin. He made occasional stays in his hometown in Iowa several months between his 1968 to 1998 Alaska life, and had increasing social contact as awareness of his life and project grew. From the beginning, an old pilot-friend flew in food and supplies on a regular basis over the years, permitting Proenneke to perfect his wilderness situation and stay in his beloved cabin year-round. Eventually his stay extended to 30 years.

Keith's reconstructed journals -- which Proenneke appreciated but acknowledged to often be a paraphrase of his rough notes -- reveal parallels to wilderness philosopher Thoreau, whom Proenneke read and admired, along with Aldo Leopold. As editor Branson puts it,

The more one examines Proenneke's life at Twin Lakes, the more one sees Thoreau's philosophy put into practice. ... Proenneke was not a philosopher like Thoreau, but he was concerned about how the individual could find contentmnet and purpose and fit into society and nature.

Proeneke once wrote:

Somehow I never seem to tire of just standing and looking down the lake or up at the mountains in the evening, even if it is cold. If this is the way foldks feel inside a church, I can understand why they go.

And when he returned from the mountainside once, he felt

like a man inspired by a sermon that came to me firsthand, that came out of the sky and the many moods of the mountains. ... Everywhere I looked was fascination.

As his fame spread in the 1980's, Pronneke took on more formal tasks, volunteering for and eventually being employed by the National Park Service while living in his cabin. He is more distracted by filming and Park Service relations and well-meaning visitors, noisy hunters, editors seeking a writing deal, fan mail, and friends overwhelming him with gifts of processed foods. At one point, Proenneke hardly sleeps worrying about all the "garbage" of social intrusion he has unwittingly brought upon himself with the Keith book and film showing nationally.

My cabin and cache have been full to overflowing for quite some time and each new load makes me wonder where I will stow it all. ... I do apprecite everything but wish they would consider the poor miserable brush rat mmore fortunate tham they and spend their money to beat death and taxes.

The earlier years better reveal the remarkable degree of self-sufficiency that Proeneke attained in survival skills. His skills made his wilderness odyssey seem natural, inevitable, even easy. He was a sociable hermit who would not suffer in an emergency or despair in solitude. Despite his unassuming manner, he was a meticulous craftsman proud of his individual accomplishments but modest enough to keep a perspective, even in his private thoughts and in the heyday of fame.

Proenneke has good advice on what the modern wilderness hermit requires: an absence of needs, simplicity in food, enough physical exercise as a source of health, patience with weather and circumstances, making due with hand tools (with the bonus of the work increasing one's confidence). Just as important are the more philosophical characteristics: understanding the relativity of time, distance, and events, resigning oneself to the natural life cycles, and holding an appreciation of simplicity in what is beauty and pleasure.

In addition to his journals, Proenneke documented on film everything about his environment, from his cabin-building to the natural setting of his daily life. The early writings and images especially are an invaluable testment not only to one life but to the dreams and goals of the aspiring wilderness hermit.

Proenneke entered the wilderness at 51, and in 1998, at the age of 81, having stayed in Twin Lakes year-round for 30 years, entrusted his cabin to the National Park Service, which has maintained it ever since for visitors. He subsequently lived with his brother, and suffering ill health, at a nursing home, until his death in 2003 at age 86.

|

|

¶

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

BOOKS: One Man's Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey, by Sam Keith

from the journals and photographs of Richard Proenneke. Anchorage:

Alaska Northwest Books, 1999, c1973; More Readings from One Man's

Wilderness: the Journals of Richard L. Proeneke, 1974-1980, John

Branson, editor. Lake Clark, AK: National Park Service, 2006. Also

available on the web as

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/lacl/proenneke.pdf

VIDEOS: Alone in the Wilderness (2003), Alaska Silence and Solitude

(2004), The Frozen North (2006). Like the book, the video Alone in the

Wilderness covers the first 16 months, with narrative from Keith's version of Proenneke's

journal.